While being forced to watch college football’s Big 10 Championship recently, a new commercial from Humane World for Animals filled my TV screen — and I must admit, it was quite well done. However, I had never heard of this organization, so while my husband focused on the struggles of Ohio State, I did some digging and came to realize the rebranding of the Humane Society of the United States — notorious for undercover videos, ballot initiatives, and the actions of its former CEO — to the new moniker.

After a brief side quest on Google, I learned what that ex-CEO, Wayne Pacelle, is up to these days and, unsurprisingly, he’s still going after animal agriculture via his own organization, Animal Wellness Action. Upon finding his LinkedIn profile and scrolling through a few posts, this little gem stuck out at me.

Before I get too far down the gravel road on this, for those new to the animal welfare battleground and blissfully unaware of Proposition 12, let me catch you up a bit.

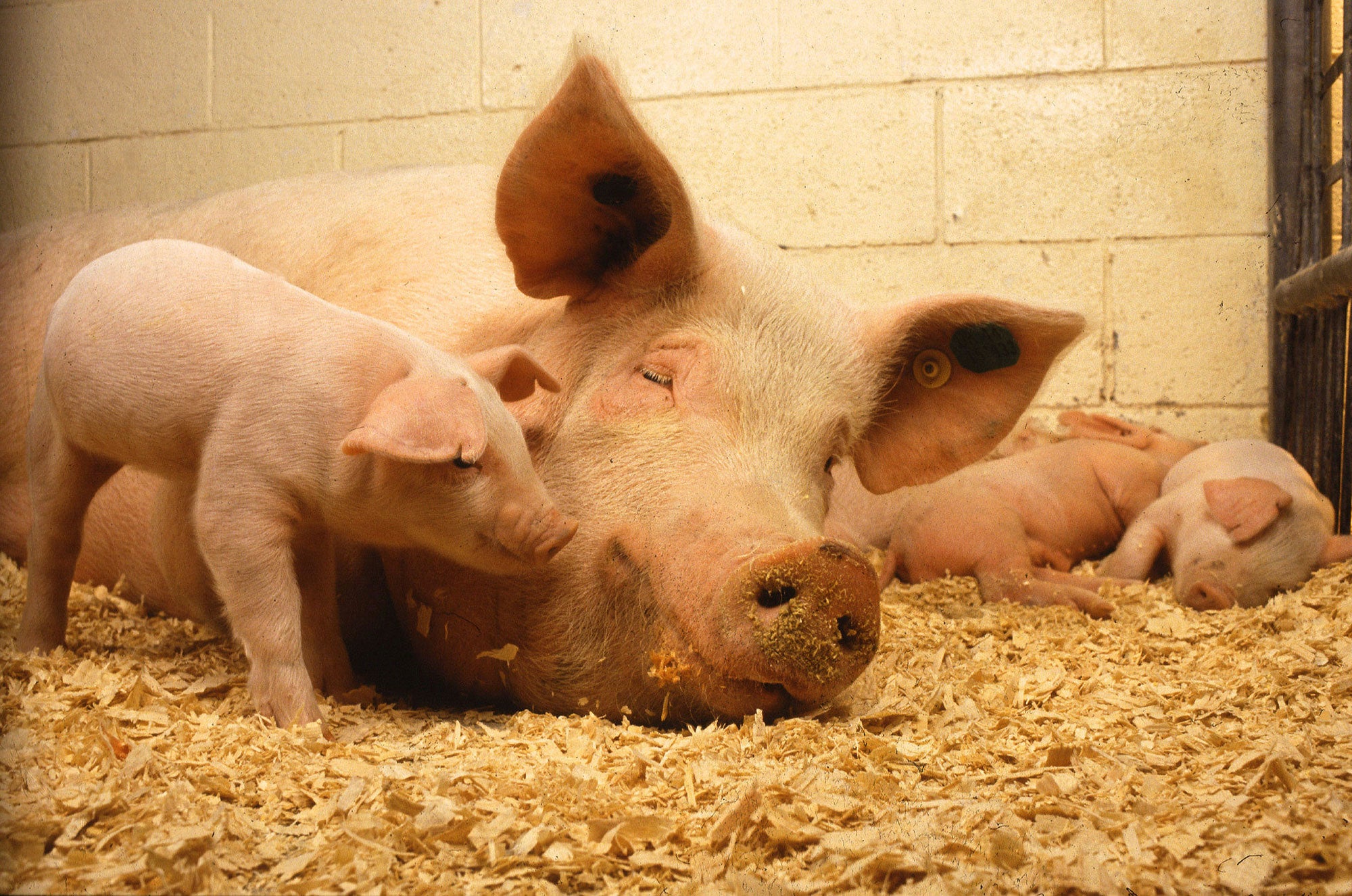

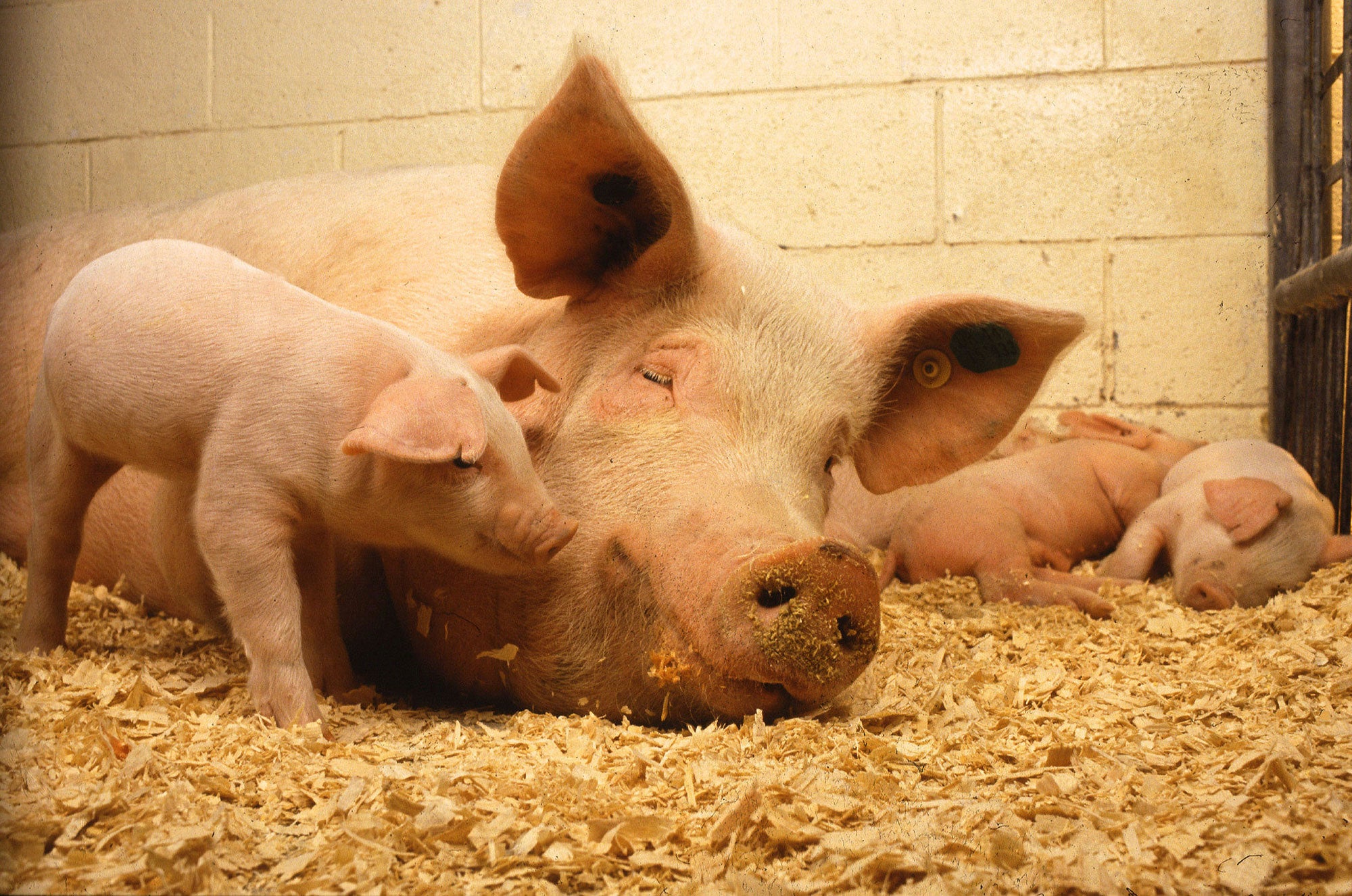

Prop 12, formally known as the Farm Animal Confinement Initiative, is a California state law that created specific minimum space for livestock such as breeding pigs, veal calves, and laying hens. Additionally, the law bans the sale of pork, veal, and eggs in California if they come from animals confined in spaces smaller than what the outlines, regardless of where they were raised. This may seem like a negligible detail, but it has massive implications for pig, dairy calf, and hen farmers who have little say in what supply chain or markets their products are funneled toward once the animals leave their farm.

The law, which originated as a ballot initiative by the Humane World for Animals (which at the time was known as HSUS) and and fellow animal-rights organization Farm Sanctuary, was voter-approved in 2018 and has had tremendous impact on the food animal industry since its implementation (it started becoming fully enforced in January 2024).

California is one of the largest consumer spending state economies, thus, farmers and retailers who want access to those consumer dollars have no other choice than to conform and remodel their housing facilities, even if they don’t live in California. That last part just really burns my bacon — I still find it unconscionable that one state can dictate the farming practices of the other 49.

Furthermore, Prop 12 sets a dangerous precedent for other ballot initiatives of this ilk, which was very likely an added benefit in the minds of its proponents. In 2024, a group of farmers and farm organizations such as the National Pork Producers Council and the American Farm Bureau Federation, sued the California Department of Food and Agriculture, basing the lawsuit on the Dormant Commerce Clause. However, the Supreme Court rejected those challenges. In June 2025, the Supreme Court declined to hear another challenge to the law from the Iowa Pork Producers Association, shuttering the pork industry’s legal fight.

Most recently, some lawmakers have set their sights on the Farm Bill to address the woes Prop 12 has created.

Both the Save Our Bacon Act and the Food Security and Farm Protection Act have been introduced as a way to mend to these issues. The latter aims to restrict state governments from imposing standards on preharvest production methods of agricultural products in another state, and the former strives to ensure the free movement of livestock-derived products in interstate commerce. Obviously, opposition exists for these bills, and animal-rights activists are already working to gain momentum to quell any “reversal” steam. Both bills have been introduced in their respective chamber of Congress and will most certainly be debated hotly.

Now back to Mr. Pacelle’s comments, posted here again to save your scroll.

The absolute audacity of this man to tout an economic argument on behalf of his preferred segment of farmers, after repeatedly dismissing every economic argument against Prop 12 in 2018, brings about a cocktail of emotions, mostly unpleasant. I know I shouldn’t be surprised but here I am, wide-eyed, slack-jawed, and annoyed.

What are those costs, exactly? According to the National Pork Producers Council, constructing Prop 12-compliant facilities costs roughly $4,000 per sow. The average United States sow farm has around 3,000 sows — you do the math. Just kidding, I did it for you. That’s a cool $12 million on average to construct a Prop 12-compliant facility (my pork industry-leader husband said I should clarify that a retrofit of a stall housing barn to a pen housing barn, instead of a new build, would be less than $4,000 per sow, but those costs vary widely).

Those costs — and whether they can be adequately recouped downstream — were a valid reason to oppose a law that many in the industry believed (and still do) was an overreach of a singular state’s right.

In 2018, pig farmers were ridiculed for using the cost of new facilities, compliance, and employee training as a reason to oppose the wide-sweeping, overarching policy. But now, Pacelle has decided he ultimately does care about economic jeopardy for pig farmers, just not all of them.

Nearly eight years ago, pig farmers were worried that consumers, who consistently vote in favor of labels and niche programs, wouldn’t pay for the more expensive niche products at the store when faced with the sticker price. This unsurprising phenomenal is called the “attitude-behavior” gap and is reported in consumer data studies annually. It’s easy to say you want a niche product that makes you feel good, but it’s an entirely different action to pay for it when you arrive at the register.

I can’t hazard a guess at what the future holds for Prop 12, pig farmers and the Farm Bill. Washington, D.C., has been a bit messy when it comes to agriculture in 2025, so it’s anyone’s best guess as to when we see a new Farm Bill, aside from the provisions included in the One Big Beautiful Bill Act. Furthermore, there is no guarantee the Save the Bacon and Food Security and Farm Protection Acts will be included.

What we do know is there are far too many people who have never had to manage land or livestock — especially under unpredictable policies and weather — who still have a lot of influence over the livelihoods of those of us who do.

Brandi Buzzard is a rancher, speaker and pioneer for modern and sustainable agriculture who blends authenticity and wit to spark ideas and innovation. She can most often be found horseback in southeast Kansas or on Facebook, Instagram or AcresTV.