When Jim Huffer died unexpectedly at 64, the farm he shared with his brother was thrown into uncertainty.

CARROL COUNTY, Indiana — Raymond Huffer never wanted his sons, Jim and Marion, to go into the family business of farming. But the brothers did it anyway.

Likewise, Jim did not want any of his three kids to go into agriculture — “I don’t care what you do with your lives, as long as it isn’t farming,” they recalled him saying. Yet soon after his passing in 2010, Andy Huffer, the eldest son, who had recently relocated from Chicago with his wife and kids, poured himself into the industry that he felt called to.

Even though Jim split his time between agriculture and a law practice, including working on wills and farm succession planning, he had no clear transition plan when he died unexpectedly at age 64 — no one besides his brother was appropriately trained on how to run the several-thousand-acre corn, soybean, and hog operation.

“I had been wanting to come back to the farm for a couple years before he passed, but he was pretty adamant that that wasn’t going to happen,” said Andy, who had spent his adult life working as an IT security specialist. “I longed to be outside. I had worked with my dad and my uncle back in high school for several summers. But after Dad died, everything was so up in the air.”

Jim and Marion — who were best friends as well as brothers — ran the farm for decades as a 50/50 business. Jim owned half the equipment, half the grain, half the bins and dryers, and half of the hogs in the barns, while Marion owned the other half. All of that was part of an informal partnership known as Huffer & Huffer. The only thing that was formally divided between them was the land.

Yet with Jim gone, Marion suddenly lost 50 percent of his stability while possessing 100 percent of the working knowledge of the land and its production capabilities.

“For my dad, being an attorney and for him doing farm-estate planning and counseling his clients through stuff like this, his will was very non-specific,” said Chris Huffer, the middle child. “He basically left everything he had to the three of us. But no discussion of how he would like for us to engage with his brother about the farm.”

Though Andy had shown interest in agriculture, there was no clear path among the three siblings because they were all already successful in other careers. Andy had been doing well in IT and just had a second child, Chris was a practicing pulmonologist in nearby Lebanon, and Abigail Diener, Jim’s only daughter, got her law degree and was working in her father’s law firm.

With Marion still involved, Huffer & Huffer now had four owners with a significant financial and emotional stake in the operation. And Marion was very aware of the power that his nephews now held over the future of the operation.

Together, they faced a difficult and complicated question: What next?

The immediate aftermath

Roughly 53 percent to 77 percent of farms today, depending on the survey, do not have written succession plans in place. And even though there is a reluctance to work with non-family members during planning, only a small fraction of those involving family make it past the second generation.

The process is tedious, complex, costly, and often very personal. It’s the kind of thing growers don’t think about when everything is running smoothly.

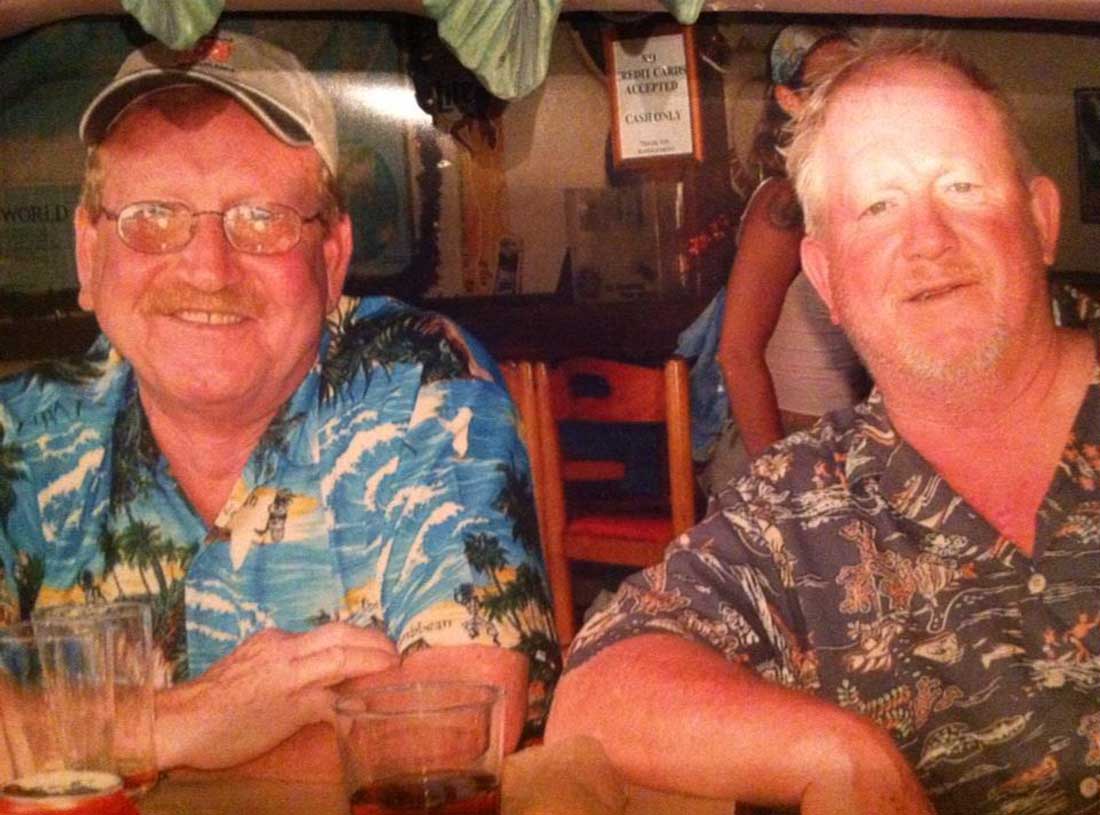

The 40-year business relationship between Jim and Marion — which included the lean and difficult times of the 1980s national farm crisis — was never plagued with major disagreements. The brothers loved and respected each other (“thick as thieves,” as the saying goes), and any difficulties they endured on the farm did not carry over to their interactions with other family members.

Yet Jim had a complicated legal estate for his adult kids to deal with, including a recent divorce.

“It definitely felt very heavy, like what are we going to do here? How is this supposed to work?,” said Abigail, who has maintained her father’s law practice in Delphi.

The siblings weren’t sure how Marion felt about the situation. He was getting older too, and there was a fractured relationship with his kids, who presumably would be in line to take ownership of the farm assets once Marion and his wife passed. Agriculture is an inherently risky endeavor, and this farm already carried significant debt.

Reluctantly, Andy, Chris, and Abigail chose to lean into optimism, despite the financial and emotional risks it promised. They entered legal discussions in April 2010 (a year the federal estate tax was repealed) with the attitude that they didn’t want to disrupt what their father and Marion had built.

“We said to ourselves, ‘We think Dad would want this legacy to keep going, right?’ We knew how much he loved his brother and how much that partnership mattered to him,” Chris said.

Dissolving even 50 percent of the farm to Andy, Chris, and Abigail was poised to be a massive undertaking and would require the siblings to apply many of the skills they had already gained during their non-farming careers.

They formed ACA Huffer LLC, a name drawing on each of the first letters of their names. That offered each of them some protection from personal liability — Chris, especially, was well on his way to being debt-free and building personal wealth through his medical profession and thus had a significant stake in the finances of the operation. The LLC meant that everything that was once owned by Jim and Marion Huffer was now owned by Marion and ACA Huffer.

Marion, for his part, was amenable and open throughout the process. He was an accountant as well as a farmer, and he offered the siblings a chance to examine the books, discuss cash rent options, and, most importantly, gave them space to decide what they wanted to do next.

“That definitely helped us because I felt like I was already overwhelmed by the stress of trying to deal with my dad’s clients and the cases he had ongoing,” Abigail said. “I did feel like we could trust my uncle completely. He welcomed us to be as involved as we wanted to be.”

She found that she would have to learn to trust Andy as well, because by the end of the summer, he had made up his mind that he wanted to come back to the farm full-time.

Becoming part of the farm operation

Jim Huffer never took a monthly draw out of the farm’s grain sales — that money went back into the business, paying down the master note, the credit line, and operating expenses.

The hog barns were different, though. They were paid off and netted about $12,000 monthly each for Jim and Marion.

Andy, Chris, and Abigail began collecting a portion of that (after paying for the animal care labor without Jim around), yet like their father, they used the grain money to continue feeding the business operations.

In all, ACA Huffer had a 50 percent share in a $1.6 million operation but barely saw any direct income remain in the bank account.

That made Chris, feeling financially vulnerable and questioning whether the operation was already over-leveraged, more stubborn than the others to take risks.

“What was very hard for me, was that through the LLC, I had to personally sign these things,” Chris explained. “My question for my own lawyer was, ‘Am I personally liable? Like if this thing goes belly up, is my house at risk? Is my personal 401k at risk?’ And he said, ‘Well technically, yes.’

“That was very hard for me to stomach,” he said. There was even a stretch when Chris wanted out of the business entirely, but Andy convinced him to stay.

ACA Huffer was luckier than others inheriting such an operation. The total debt on the farm was far less than its total value, so if disaster struck or relationships soured, the worst thing that would happen is being forced to sell everything and pay off the debts. “And even then, we’d still have a pot of cash at the end of it,” Chris added.

Yet Chris was uncomfortable with how farmers live in debt, surrounded by fluctuating balances and high dollar amounts. Chris’ trust in those around him — including in his brother who was, by now, being trained by Marion as a full-time farmer — was being tested.

“I don’t think they understood my motivations in the beginning for wanting to continue the farm,” Andy said. “And I don’t blame them for not understanding. Maybe I didn’t enunciate it well enough at the time, but I had been really getting burned out in Chicago and needed a life change.”

Abigail, too, carried some skepticism about the process but also said she was grateful that Andy wanted to be so involved in the farm’s future, even though she admits that Andy didn’t appear to have the financial management skills in those early days.

“And Chris and I both knew that,” she said.

That sentiment grew into some early conflicts — especially between Andy and Chris — when Andy wanted to buy more land or expand the operation in other ways. Chris was his roadblock in many instances.

Abigail often had to position herself as the peacemaker between her brothers.

“Those first couple years was a lot of feeling overwhelmed, feeling like I didn’t know what was going on,” Abigail said. “And though I didn’t fully know what was going on with the farm, I didn’t really want to rock the boat either.”

As siblings, they all had to talk — to have real and meaningful conversations — to adapt to the situation and avoid resentment.

It became clear that the lynchpin to the farm’s future was Andy. Marion’s kids weren’t showing an interest in taking a leadership role at the farm, and Andy at least had the drive to learn and build upon his high school years working part-time along the combines.

Growing into his own on the farm

In the 20 years since those high school days, modern agriculture has changed significantly. Autosteer was added to the machines, the planter went from eight rows to 36 rows, and seed varieties and crop protection chemicals improved.

“Things had changed so much that I might as well have been brand new,” said Andy, who spent the years between 2009 and 2015 hooking up PPO shafts, working ground, learning how to drive a truck rig, understanding agronomy, paying attention to the marketing plan, and building the foundation to one day manage the operation.

That included some of the farm’s old-timers pushing him into the worst kinds of tasks.

“They’d throw me in the mix and say, ‘Andy, you got to do that because it’s hard and because it sucks,” he said.

That meant, for example, being the one to climb 150 feet to the top of the large grain system — even in tough weather conditions. “If I want to keep this farm going, if I want to keep making progress, if I want to keep paying my employees, if I want to keep doing this kind of lifestyle, I have to endure that kind of pain and that kind of fear,” he surmised.

In 2014, when ACA Huffer agreed to purchase a piece of a neighbor’s land, that helped give credibility to Andy and his siblings in the eyes of Marion.

“I think that made my uncle respect us a lot,” Chris said, “and made him feel that we were here to be his partners.”

Marion knew the operation and was great at the detail and paperwork sides of it — even if he was more of a pencil-and-paper guy instead of a digital-records one. But over the years, he “wasn’t inherently the best teacher,” Andy noted.

So, Andy had to draw on a lot of his previous IT skills to manage the farm from the business end and reverse engineer a lot of the data. The numbers he achieved were the same as Marion’s, just fleshed out in a different way.

In a sense, Andy updated the process of managing 6,000 acres and six employees to make it his own.

That helped him in the years leading up to Marion’s death in 2019, when Andy had begun entirely running the farm, amid some tough seasons. He discovered what central Indiana agriculture was like through these trial-and-error moments.

“I am still really thankful that I had those nine years with him,” Andy said, “not only to get out of my green status as a farmer, but from an operational point of view, just turning wrenches and being able to pick his brain to the extent that I was before he passed.

“Otherwise, I don’t know that we would’ve survived,” he added.

Andy adopted some of the more innovative ideas on the farm, like utilizing variable-rate planting and residual herbicides — opting to forgo half a dozen seasonal passes of Roundup. The swine operation has also expanded in recent years. Andy explains having “finessed and fine-tuned” some of Marion’s better qualities to help make the farm successful.

“I’m learning new stuff every single day,” he said. “That’s still the case.”

The post-COVID era and the future of the farm

Rural twentysomethings are consistently less likely to return to their home communities after college — a phenomenon known as “brain drain” — because of the promise of better job opportunities and higher salaries in urban areas. But for Jim Huffer’s kids, all of them eventually found their way back to Indiana’s Carroll County.

The siblings ultimately decided to split up their share of the farm’s assets — Chris and Abigail got most of the land while Andy got all of the equipment and structures, such as the barns and bins. The distribution was amicable, though Andy was in the least stable position, as machinery requires maintenance, depreciates, and can be difficult to liquidate. Meanwhile, land values rise annually.

Andy’s livelihood is on the farm, and the machinery meant more to him than it did to the others. But all still support the work being done today on what was once their father’s farm, and it is incredibly important to Chris and Abigail for Andy to succeed and that his livelihood is protected.

“If you were to ask me who I trust most in the world, it’s hands down my brother and sister,” Andy said. “I can tell them anything. They are my two absolute best confidants.”

They shared all of the annoyances, frustrations, and anger that come when a farm lacks a clear succession plan. Huffer & Huffer wasn’t alone in that — experts say that too few farmers and ranchers spend time planning out generational transitions.

“The younger generation often isn’t being included in the real nuts and bolts of how stuff works and who gets what,” Abigail said. “They always think they have more time.”

Luckily for Huffer & Huffer, a successor felt called to carry on the legacy and prove that he wasn’t into farming for the 2 percent of luxury time basking in the sun and listening to the birds chirp. He was in it for the 98 percent of the time when it’s miserable.

“Farms are dying off every year, and there are a variety of reasons for that,” Andy said. “My father and uncle built something really special and back in the day — they were the kingpins in this county. I was proud of that, and I wanted to continue to be proud of that.

“And I didn’t want it to fail.”

Ryan Tipps is the founder and managing editor of AGDAILY. He has covered farming since 2011, and his writing has been honored by state- and national-level agricultural organizations.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc()/44467609092_de0dd33a28_o-ea570461a64240d9bdad9717b3374b48.jpg)

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc()/Markets-2-Storm-candlestick-up-9-4bd8982c0a6b4c0e9e01a0d2bcb070ed.jpeg)