Depending on which side you believe, rural America is about to either suffer the loss of a record number of hospitals or be infused with the largest fiscal investment in two decades. As with everything political these days, the dichotomy is too stark to span with hearsay alone.

I have to admit it was a bit jarring to see a list of 12 “at-risk” hospitals in Indiana, with my own hometown’s Ascension St. Vincent Clay Hospital in Brazil smack dab in the middle. Also, on the list is neighboring Sullivan County Community Hospital. Meanwhile, the two hospitals in our other neighbor, Vigo County — Union Hospital and Terre Haute Regional Hospital — plod forward in their challenged plans to merge into one entity.

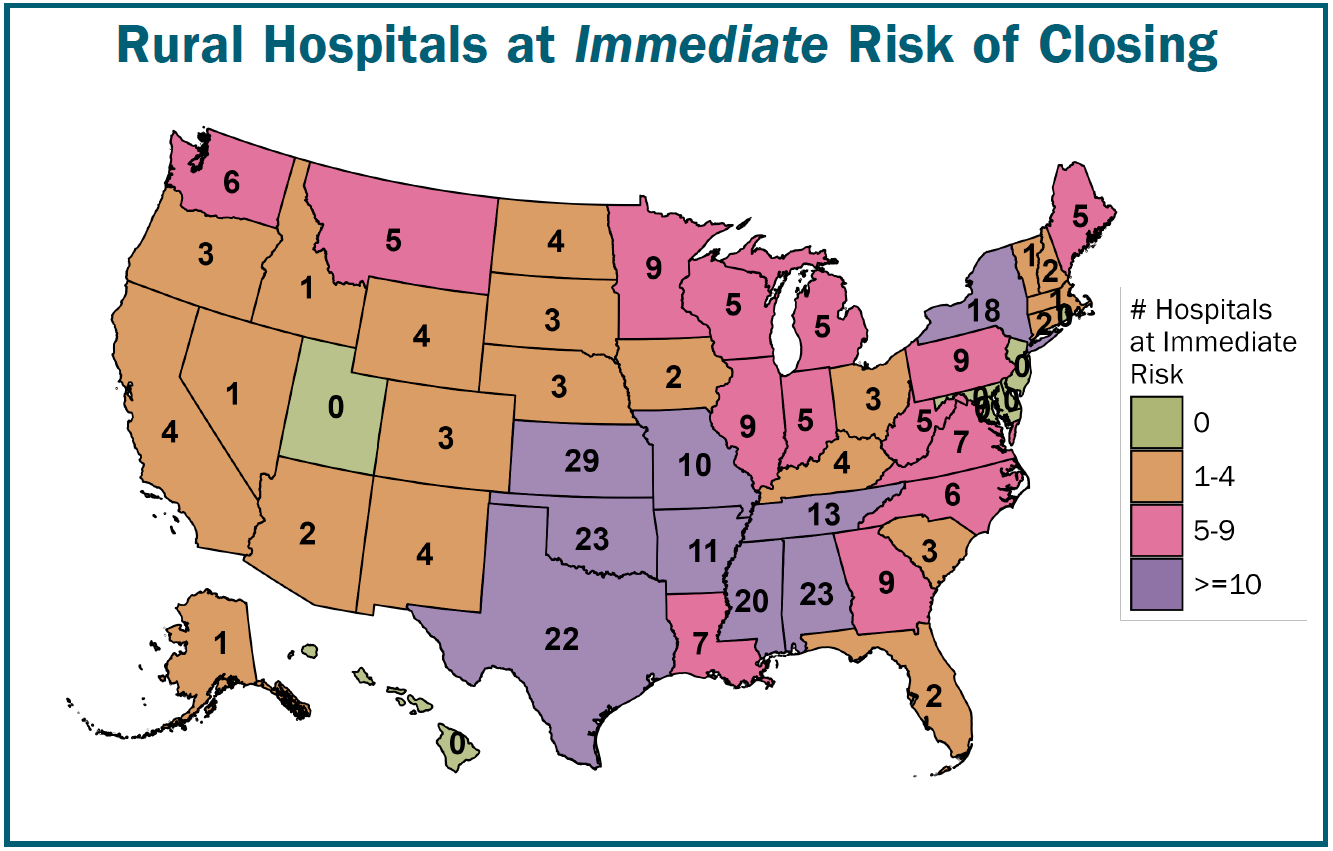

All totaled, 338 U.S. hospitals have been placed on an “at-risk” list for closure, ostensibly due to proposed Medicaid cuts involved in the One Big Beautiful Bill Act, recently passed by the Trump administration.

Meanwhile, the Republicans counter that the $50 billion funding included in the Act’s Rural Health Transformation Program will not just help rural hospitals, but in fact transform them with the largest single investment since the Medicare Modernization Act of 2003.

And while to some these numbers might seem minor relative to the 6,093 hospitals in 3,143 counties in the U.S., to the more than 60 million folks living in rural America, it’s a big deal indeed.

To me, it’s a much longer story than the simple passing of one bill proposing cuts to Medicaid. I see this as very similar to the phenomenon facing small, rural churches and other key infrastructure and community elements in “flyover country.” It’s also akin to differing needs and sometimes contrasting perspectives between large agricultural producers and small family farms.

Complex problem

Right off the bat, there’s broad agreement that rural hospital closures are not the fault of Medicaid cuts alone, nor are they to be blamed on the uninsured.

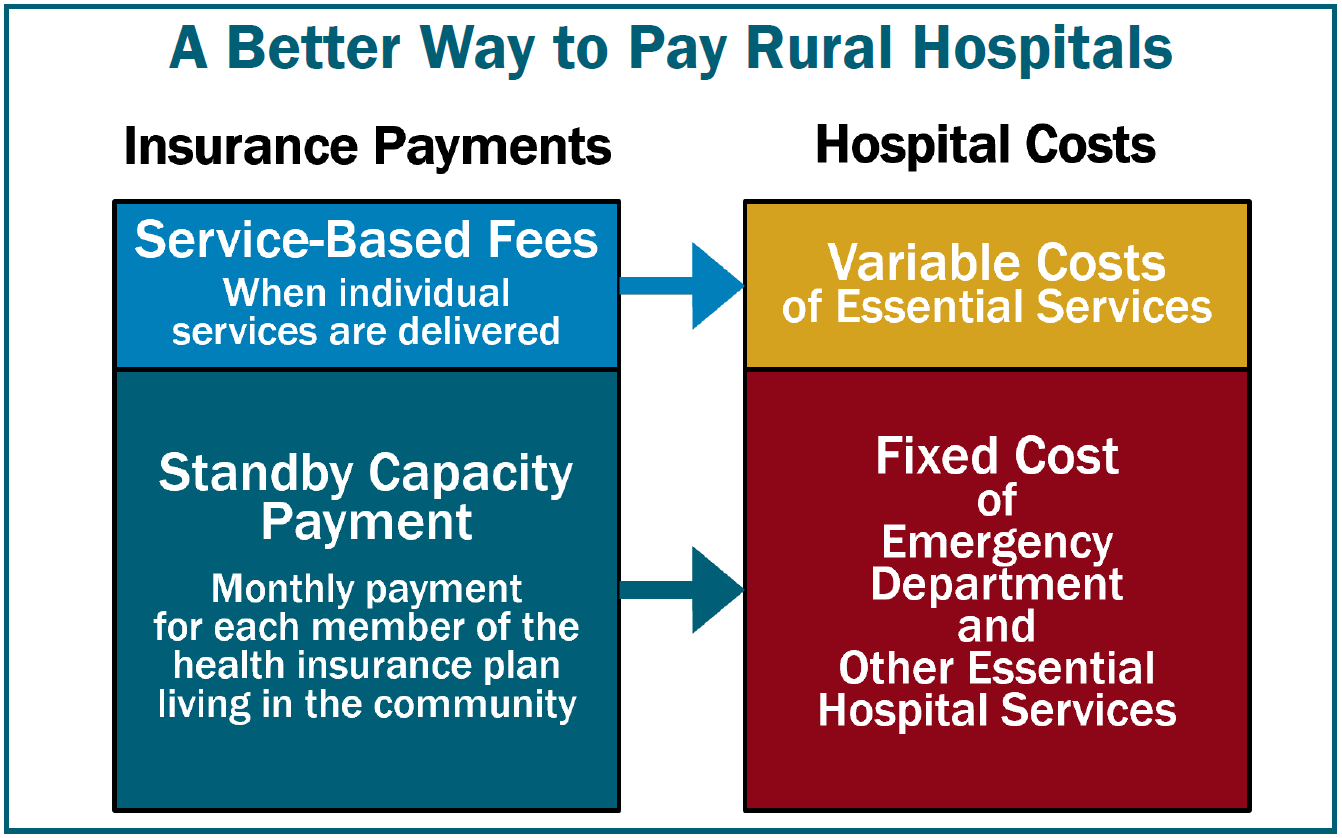

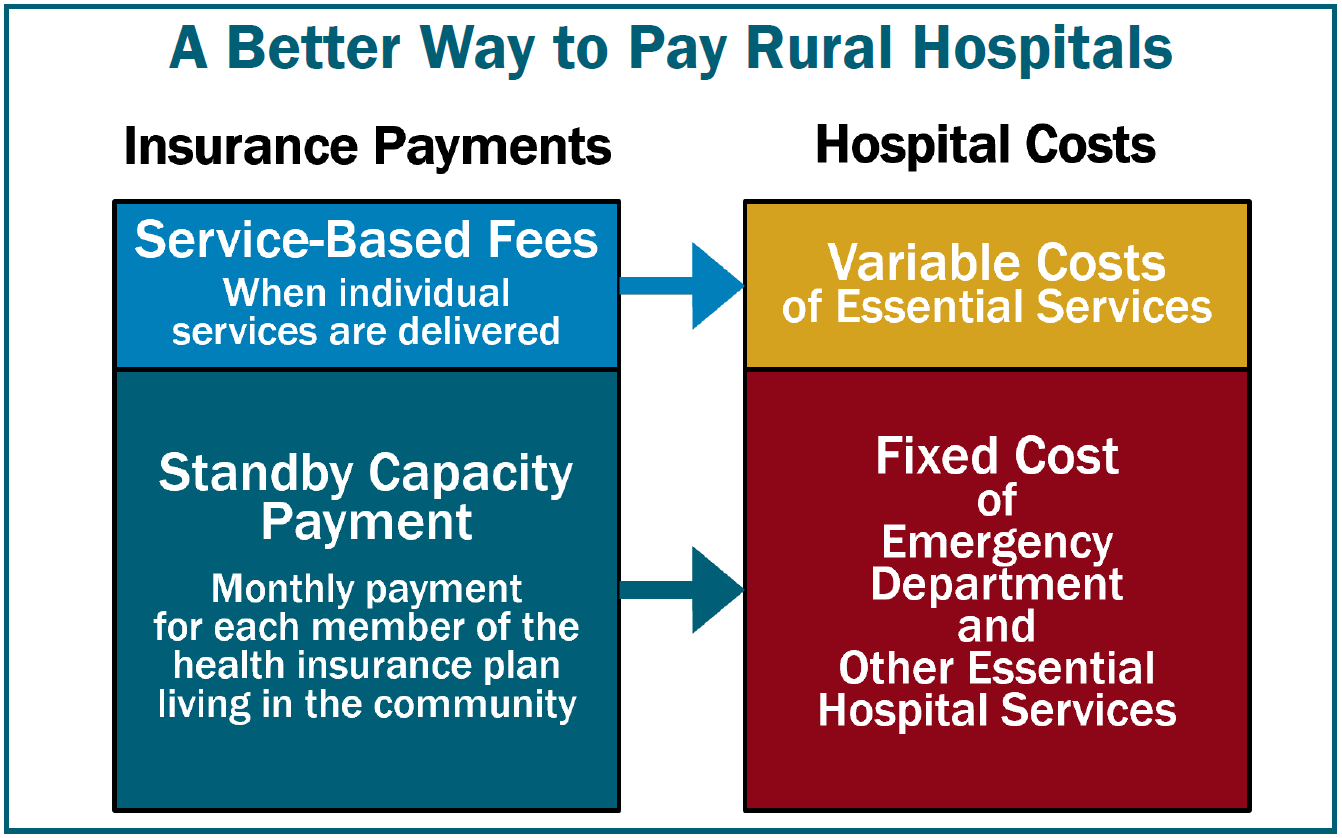

According to the Center for Healthcare Quality & Payment Reform (CHQPR):

“The primary reason hundreds of rural hospitals are at risk of closing is that private insurance plans are paying them less than what it costs to deliver services to patients. Although the at-risk hospitals are losing money on uninsured patients and Medicaid patients, losses on private insurance patients are the biggest cause of overall losses. … Most solutions for rural hospitals have focused on increasing Medicare or Medicaid payments or expanding Medicaid eligibility due to a mistaken belief that most rural patients are insured by Medicare and Medicaid or are uninsured. In reality, about half of the services at the average rural hospital are delivered to patients with private insurance (both employer-sponsored insurance and Medicare Advantage plans). In most cases, the amounts these private plans pay, not Medicare or Medicaid payments, determine whether a rural hospital loses money.”

So why is this? Why do private insurance companies — such as Aenta, Cigna, or Wellpoint — not reimburse rural hospitals well? Since 2010, 130 rural hospitals have closed, so the good news is that the phenomenon is well documented and studied, if a bit complicated. But it all comes down to the self-fulfilling prophecy that all small-town businesses, churches, and even farmers understand all too well — “bypass behaviors.”

Folks in small, rural towns who have good commercial insurance choose to take their medical business to the larger institutions elsewhere. The more business they take out of town, the fewer services the local facility can afford to offer. The fewer services the local facilities offer, the more people with means shop out of town. And this is why private insurers reimburse small, rural hospitals less. Because they can. The smaller the hospital, the less leverage it has in negotiating with larger companies.

Size definitely matters when it comes to reimbursements, as each insurer pays a different contractual rate to each facility. In an example offered by Harold Miller, president and CEO of CHQPR, one rural hospital in Alabama gets paid $65 for an X-ray by Blue Cross and Blue Shield of Alabama, but gets $97.03 by Aetna for the same service. Miller went so far as to say, “Alabama Blue Cross could single-handedly save all the rural hospitals in Alabama. It just has to pay adequately.”

The reason for the disparity is Blue Cross and Blue Shield of Alabama has so many more insured relative to Aetna in that area they can command a much lower price. Small communities tend to have higher concentrations of patients covered by the same insurer, hence the disparity. But what is an “adequate” price when it comes to X-rays? Irrespective your answer, the smaller hospitals typically lose in the negotiations, and larger facilities wind up attracting better insured customers. The result of this spin cycle is that small, rural hospitals serve a customer base disproportionately poor and limited in options.

Therefore, any cuts to Medicaid are perceived to be a worsening of that problem, and it’s true, any cuts in revenue to a bleeding facility will indeed hurt.

Transformation continued

Republicans counter that their Medicaid cuts will be offset by the Rural Health Transformation Program’s $50 billion grant program, which will distribute the funding among the states via an application process with the U.S. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Participation in the grant program will be subject to the approval of specific plans for the funding.

The development of more high-tech options like AI-powered mobile clinics as well as outcomes-based improvement plans is in the mix there.

The fact is, the business community in small, rural towns has been changing for years. Whereas the town of Walnut Grove as depicted in Little House on the Prairie featured one general store owned by a single family, today these same towns have major chain retailers ranging from Rural King to Home Depot, with more people than ever shopping Amazon.com. The same is true with healthcare. In the 1950s, patients with a broken arm would spend weeks in the hospital as the bone set. Today, broken bones can be cast in a matter of minutes in a private doctor’s office.

Likewise, imaging and lab work is quite often outsourced these days. This puts a burden on the smaller hospitals that have to maintain the same costly infrastructure while being utilized for fewer services — and often poorly reimbursed when they do complete services that they are able to. Meanwhile, the buying power of the larger hospitals continues to help them grow, while also helping them leverage better reimbursements from private insurers.

Still, rural hospitals are economic anchors within their communities, often doubling as major employers. The potential impact of job loss alone can produce a ripple effect throughout the community, as well as diminish its standing in terms of quality of life as people wonder whether they want to move to a county that has no hospital.

And it’s lost on no one that if present Medicaid patients lose that healthcare coverage, they’ll wind up having costing some other hospital more money as uninsured.

I can see this in the rural Indiana community in which I live. If the hospital in my own Clay County were to close, the emergency department would also close along with it. What patients do go that hospital would then have to be transported to next-door Vigo County whose two hospitals are now considering merging into one. If Sullivan County, which is just south of Vigo and east of Clay, loses its hospital too, that’s going to be a lot of patients being funneled into the same organization, all with differing capacities to pay. My guess is a lot of lower-income people will simply go without care for lack of transportation if that occurs.

But, irrespective of the One Big Beautiful Bill Act, I think this has been occurring right beneath our noses for years, and the RHTP isn’t going to change that.

Brian Boyce is an award-winning writer living on a farm in west-central Indiana.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc()/AJF_3081-2048x1366-9f62d4aadc4b42c9a1370f396a7c2f64.jpg)

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc()/20250812_191119-2048x1536-6eb6a29df1f544498ebbba9d26b252bd.jpg)

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc()/49023237277_bacbbd53bb_6k-333e181f8c634be39d7fe38c1d50ba54.jpg)