Colorado has been ground zero for policy surrounding wolf reinductions, where the emotional and financial toll on livestock producers is reaching a tipping point.

Editor’s Note: This is the first in a three-part series exploring the impact that wolf reintroduction in the U.S. has had on livestock operations. Caution: This article includes graphic images of livestock carcasses.

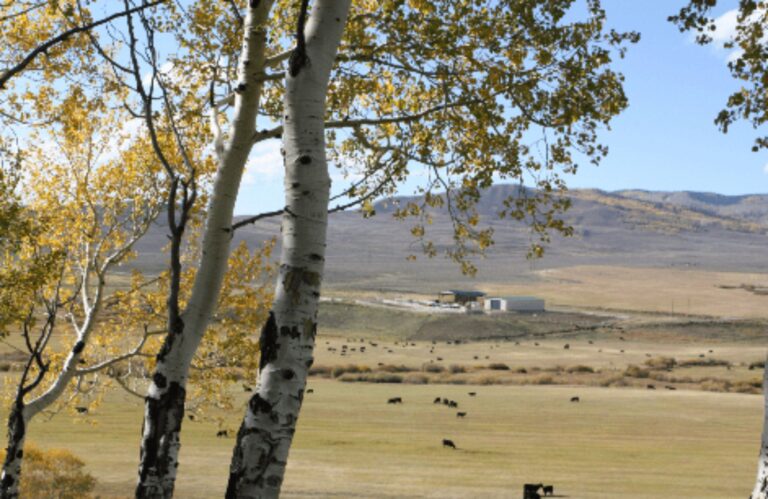

At Coberly Creek Ranch in Routt County, Colorado, Merrilee Ellis had just found another dead calf. Three days after Ellis and her family trucked their calves home and turned them into the hay fields, this animal’s body laid half-eaten in the spring snow. Only hours earlier, a Colorado Parks and Wildlife employee texted that a collared wolf was in the area.

To Ellis, the depredation was yet another stain on the state’s efforts to reintroduce predators on lands worked by ranchers and frequently grazed by vulnerable livestock populations.

The Ellis family runs a cow-calf and hunting operation on forest permits and private land in northwestern Colorado. Since wolves were released near their ranch in late 2023, they’ve seen confirmed and suspected depredations, a spike in missing calves, and a sharp drop in conception rates.

Beyond the dollars, Ellis describes a grind that’s devastating: calling in a kill, rushing to document possible evidence before weather erases all signs, then bracing for another “inconclusive” response from officials. She also calls the ranch vet to the site, clips hides to reveal scrape and bite marks, and catalogs evidence, but says the cycle still feels stacked against producers.

When Ellis told the ranch manager which calf it was, she said he “just got despondent — he knows the mom, he knows the potential of this calf. … When you see how they’ve been torn apart, it’s very emotional.”

After a suspected depredation, the rancher is expected to secure the site and quickly contact the state’s wildlife agency. Investigators then meet the rancher at the scene to document the case: photograph the area, look for a “fight scene,” and track sign (wolf, coyote, bear, mountain lion). At the carcass, they are supposed to clip hair to expose wounds, measure canine spacing with calipers, and skin back the hide to check for subcutaneous hemorrhaging — blood under the skin that shows the animal was alive when bitten.

Those steps help rule predatory species in or out and determine whether the death is “confirmed,” “probable,” or “inconclusive” from such a predator. Only after that determination can a producer file (or complete) a compensation claim; in Colorado, producers typically file an initial claim within 10 days, then add records (missing stock, conception rates, weights) before year-end. In practice, written investigator reports often arrive after a claim is opened.

When the investigators arrived that day in April 2025, Ellis says they quickly ruled out everything except wolves. They agreed the calf had been killed by a predator, said it was too large for coyotes and didn’t match a bear or lion, and pointed to other sign. Ellis, however, acknowledged being jarred that the investigators didn’t bring the basic tools needed for a necropsy.

“They didn’t have clippers, which is really important,” she said, adding that they didn’t bring a measuring tool to gauge the distance between canine tooth bites. “We didn’t clip the hide where you can see little scrape marks and measure canine distances.”

Ellis added that a measuring tool is something that has been missing during every depredation investigation on her ranch. Without being able to see and measure the wounds properly, especially with scavengers trying to feed on the carcass, timeliness is vital to obtaining evidence.

Ranchers argue that waiting too long makes a wolf confirmation nearly impossible and all but guarantees an “inconclusive” ruling.

In this case, Ellis said the investigators agreed the calf was killed by a large predator but also that she was told: “ ‘We’re just not sure if we can conclude it was a wolf.’ Those were their exact words.”

Days later, CPW informed the ranch that the case would be ruled “inconclusive,” a decision that meant no confirmation on the official depredation list and no payment from the state’s wolf compensation fund.

AGDAILY contacted CPW twice requesting comment, though no reply aside from confirmation that the request was sent to the agency’s public information officer was received prior to publication.

Complications of claims

Decisions about depredation claims happen within the legal framework of the Endangered Species Act.

Under a special Endangered Species Act 10(j) Rule “experimental population” rule finalized in December 2023, Colorado wolves remain protected, but the state can take limited action when conflicts occur. That can include nonlethal measures to push wolves away from livestock and, in narrowly defined cases, lethal removal after repeated attacks. Mexican gray wolves in Arizona and New Mexico are managed under a similar framework, with comparable rules governing investigations, compensation, and response.

The lynchpin that ranchers are faced with is that ESA status shapes what ranchers, states, and federal agencies can do after an attack, and it’s why the wording on an investigation form matters so much.

Federal policy is also moving underfoot. In November 2025, the Trump administration proposed ESA rule changes to realign with the 2019-2020 framework, emphasizing “clarity” and “predictability,” and allowing economic impacts to be weighed in listings and critical habitat decisions. That debate looms over every depredation fight because it influences future protections, flexibility, and funding.

Ellis said compensation claims require ranchers to document three-year averages of calf deaths and missing losses before wolves are present.

“Most ranchers lose 3 [percent] to 5 percent of their calves in the first month of life for reasons unrelated to wolves,” she said. Before wolves were established on the same grazing permits, her ranch averaged a 5.7 percent death loss and a 1.1 percent missing loss, or about 5.5 calves annually, which Ellis attributed to disease, weather, or other predators.

“Since the wolves have been introduced, that number has skyrocketed,” she said. In 2024, overall death loss remained steady at 4.9 percent, showing no increase Ellis attributed to wolves, while missing calves rose to 8.5 percent.

“We went from averaging about 5.7 missing calves to 44 missing calves, which resulted in a $92,000 loss this year,” she said. The state recognized 14.5 indirect losses above the established baseline.

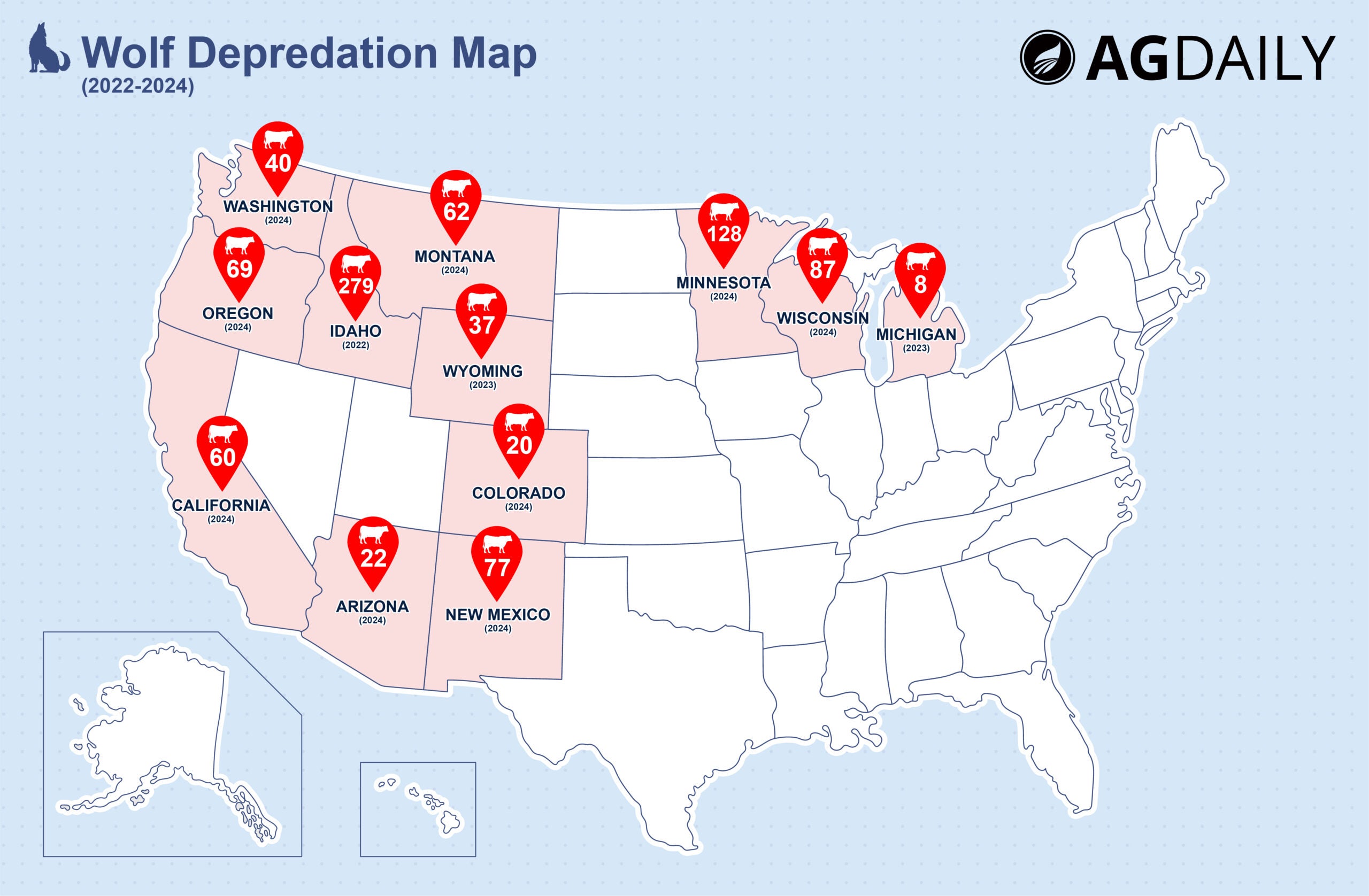

Other Colorado ranches have sought to recover more than half a million dollars in compensation.

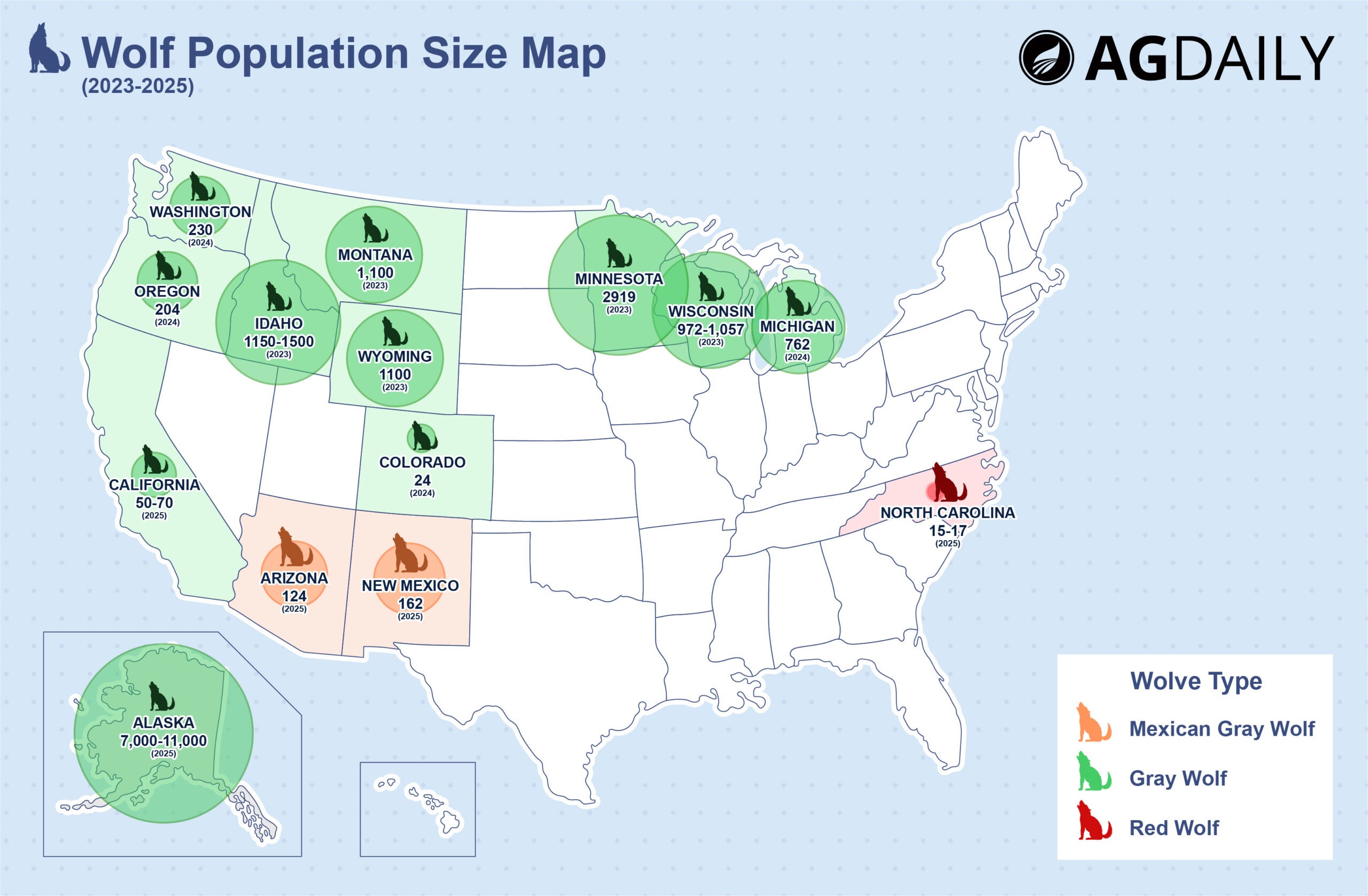

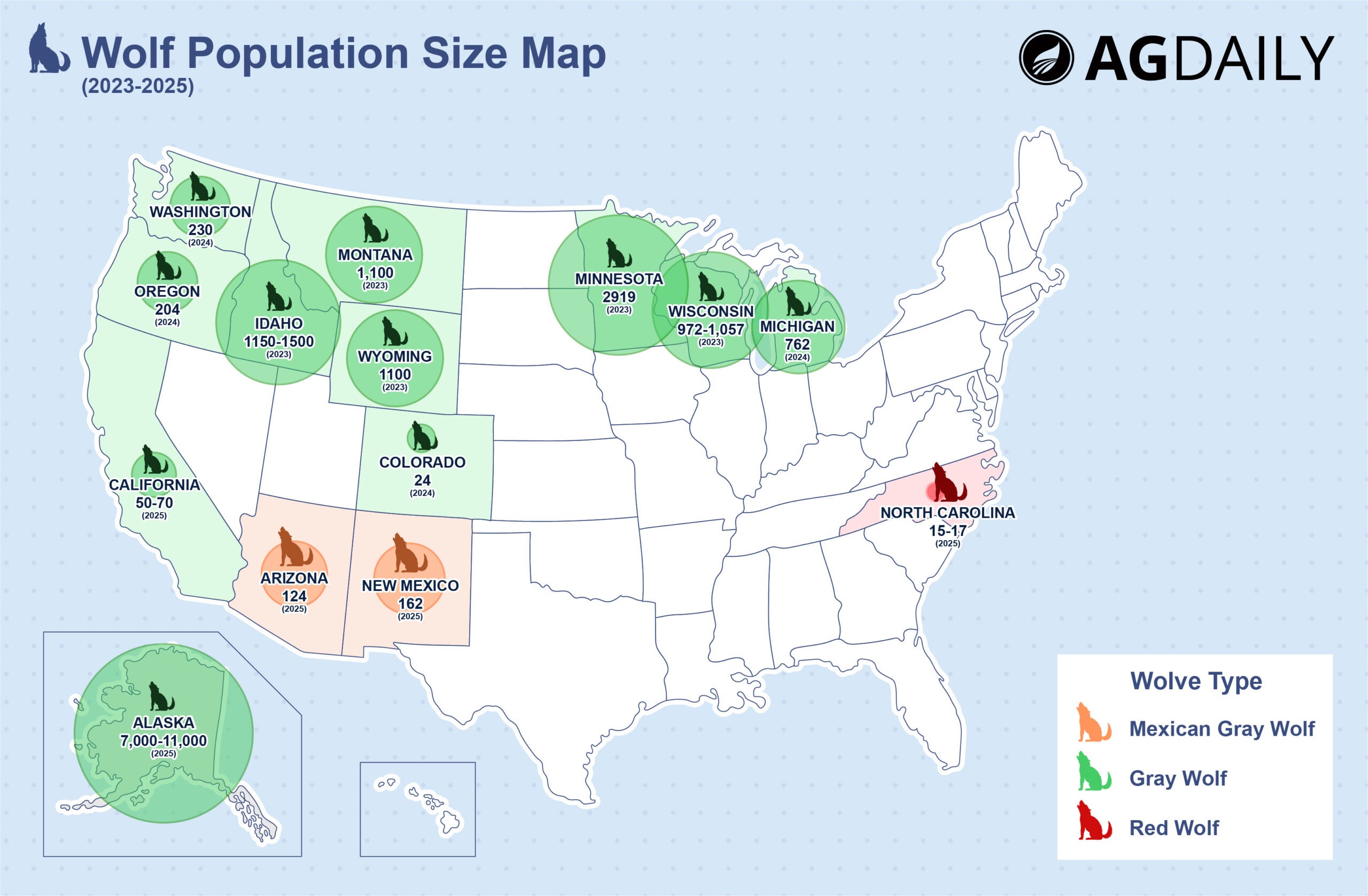

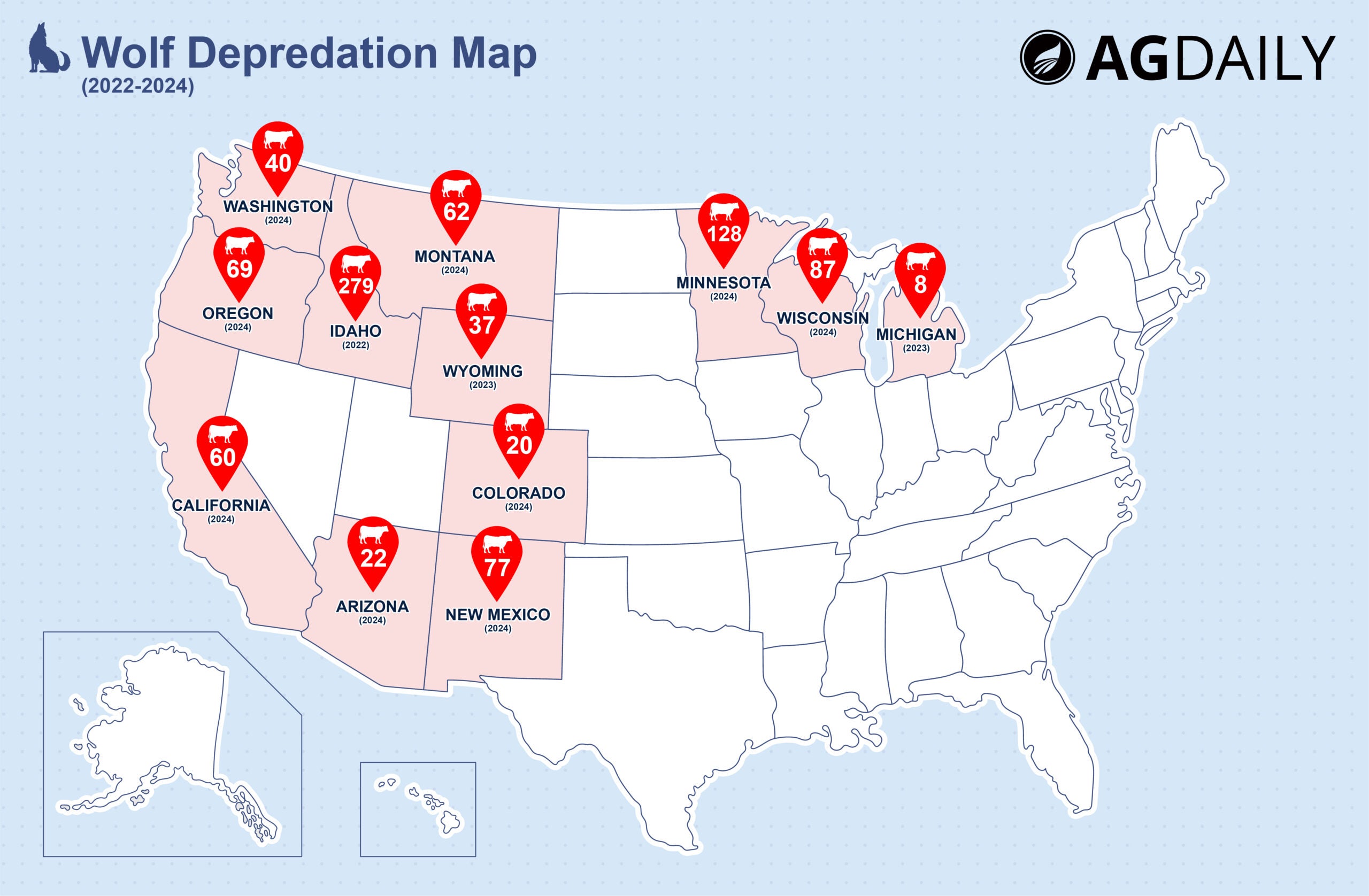

Across the lower 48 states, an estimated 20,000 wolves are currently on the landscape. Most are gray wolves (Canis lupus), which make up the vast majority of populations in the Northern Rockies, Great Lakes, and Western states. In Arizona and New Mexico, a distinct subspecies, the Mexican gray wolf (Canis lupus baileyi), is managed separately under its own recovery program. North Carolina is home to the critically endangered red wolf (Canis rufus), a different species with a much smaller and more limited population.

However, exact data can be difficult to come by, as wolf population and depredation figures vary by state and reporting schedule.

Some states have updated counts from 2023, while others rely on data from 2024 or early 2025. This article uses the most recent publicly available estimates for each state, with dates clarified in the text where relevant. In some cases, population data reflect estimates reported between 2018 and 2023 due to differences in monitoring and publication timelines.

During an interview with TV station 9NEWS in August, CPW Director Jeff Davis addressed the number of wolves the state currently has, saying, “I couldn’t tell you, like, oh, it’s 34 or something like that.’ The math is hard when it’s day to day.”

In 2025, once cattle came off forest permits, the Ellis family counted 40 missing calves, which, using the same baseline, implies 34.5 above-average losses. At roughly $2,500 per head, Ellis says even the portion the state recognizes “feels massive” compared to what used to be a normal year.

Beyond the immediate calf price, each loss cascades through the whole herd economy. A dead or missing calf isn’t just one year’s revenue; it also means the cow that lost that calf is more likely to come up open the next season and her weaning weights tend to sag under stress. Additionally, a rancher has already sunk extra labor, vet time, and predator-deterrent costs into animals that won’t pay back this year.

Replace those animals and a rancher ends up tying up capital in heifers that won’t calve for 24 months, as well as setting genetics and cash flow back another cycle. That’s why the ranch values a single animal unit over its working life, not just at the current market for one calf, but thousands in lifetime value, reflecting six to eight calf crops, cull value, and retained-heifer potential. Viewed through that lens, a jump from a three-year baseline of 5.5 missing calves to 20 (2024) and then 40 (2025) isn’t a $2,500 line item, it’s a multi-year hit to revenue, reproduction, and replacement that compounds across the herd.

“When you bring all these cattle in and you realize you’re missing 40 calves — that’s just overwhelming,” explained Ellis. “We couldn’t lose 20 percent of our cows a year to non-pregnancy and 40 calves every year. We couldn’t do it.” Additionally, she said that the ranch’s calves that used to come in at normal weights are now 20 to 25 pounds lighter.

“The indirects are going to be prohibitive for the state of Colorado if all of the ranchers that are truly impacted put together the billing,” Ellis said.

So, when a CPW wildlife damage specialist phoned back to warn the family they “weren’t going to like” the official decision on that April calf, Ellis’ son-in-law hit record on his cellphone.

In that nearly 20-minute call, reviewed by AGDAILY editors, the investigator acknowledged the calf had clearly been killed by a predator, described the drag marks again, and confirmed that a collared wolf, identified as wolf 25-10, had plenty of time to be at the carcass and back to where its GPS collar later pinged.

“They all know that I think it’s a wolf,” the investigator on the recording said, referring to the most recent depredation investigation, and CPW employees, “everybody’s telling me I have to call it inconclusive … and if I don’t call it inconclusive … they’re going to argue with me. … I’m not ruling out wolf. They all know I think it’s a wolf, but I just don’t have enough evidence.”

When Ellis and her attorney later reviewed CPW’s written report to the wildlife commission, they were stunned to see a completely different story: It said the calf “probably” died of high-altitude disease a few days after arriving, with no predator involved, and the ranch was described as having an “unhealthy” herd based on four calf deaths over 22 months — deaths Ellis says were all wolf kills.

“Any wolf person can tell you that in a four-hour period, a wolf can travel a long distance, eat 20 pounds of the calf, and get back,” she said.

The recording made that discrepancy impossible to ignore. After the audio was turned over to state officials and reporters, CPW reclassified the case as a wolf kill and paid the claim, the ranch said.

“It definitely presented new circumstances into our consideration,” Davis said. “It presented a piece of information where we were hearing that the staff maybe had differences of opinion.”

Davis resigned on Nov. 22 while on administrative leave.

Confirmed vs. convenient

The about-face rattled producers across Western Colorado and fueled a deeper worry: If one case could be steered away from a confirmed wolf depredation, how many more might be quietly shifted into the “inconclusive” column?

Ellis says one neighbor near the King Mountain Pack in Routt County reported 10 likely depredations this year, yet the first nine were officially ruled inconclusive, despite the wolves being within a mile of the herd. Only the 10th was confirmed as a wolf kill.

Those concerns didn’t come out of nowhere. Long before Colorado’s first truckload of reintroduced wolves was unloaded in December 2023, stockgrowers’ groups were already fighting the program. The Colorado Cattlemen’s Association and Gunnison County Stockgrowers Association went to federal court earlier that year, arguing that the reintroduction plan didn’t adequately consider impacts to livestock and rural communities; a judge let the releases go forward but acknowledged the concerns and pointed to the state’s compensation program as the main safety net.

Since then, local stockgrowers associations have been on the front lines of the conflict. Middle Park Stockgrowers and others helped producers assemble hundreds of thousands of dollars in wolf-related damage claims, a combined $575,000 to $582,000 bill for missing calves, dead livestock, and lighter weaning weights that would nearly drain Colorado’s Wolf Depredation Compensation Fund in a single year.

Ranching groups also petitioned CPW to pause further wolf releases until conflict-mitigation tools and funding were fully in place, but in January 2025 the wildlife commission voted 10-1 to deny that request and keep the reintroduction schedule on track.

From her place on the ground, Ellis sees the policy debate through the lens of record-keeping, necropsies, and long days riding 20,000-acre forest permits looking for dead calves.

“It is mind-blowing how much time we’re putting into this,” Ellis said. “We have incredible records, I can go back to 2005 — but it’s still time-consuming to put it all together.”

Social science research out of Colorado shows that the reintroduction effort’s ecological promises — and fears — are exactly what get weaponized in public debate. In a 2022 study, Rebecca Niemiec and colleagues tracked opinions before and after Colorado’s wolf ballot and found that support for reintroduction dropped from 84 percent in a 2019 survey to about 64 percent in a post-election survey, even though the measure still narrowly passed statewide.

The same study found that the top reasons people supported wolves were “restoring ecological balance” and a moral duty to “right a past wrong,” while the top reasons for opposition were concerns about livestock, elk and deer impacts, and cost – mirroring the fault lines between hunters, ranchers, and urban voters.

Niemiec’s team also showed how fast perceptions can shift. In just over a year, Coloradans became more likely to believe wolves would cause “large numbers of attacks on livestock” and big losses in deer and elk, and less likely to believe wolves would simply bring ecosystems back to their “natural” state. Local news was the most commonly cited information source, underscoring how media framing — not just biology — drives the wolf-as-ecosystem-fix narrative and the backlash against it.

Heidi Crnkovic, is the Associate Editor for AGDAILY. She is a New Mexico native with deep-seated roots in the Southwest and a passion for all things agriculture.

Jake Zajkowski is a freelance agriculture journalist covering farm policy, global food systems and the rural Midwest. Raised on vegetable farms in northern Ohio, he now studies at Cornell University.