Entwined within the societal issues being addressed these days is that of declining college enrollment, and agricultural programs around the country are in the thick of the discussion. Hardly a secret, the long-dreaded demographic cliff is creeping onward, and in some cases, it’s a very clear issue of numbers: Fewer people, fewer students.

Earlier this summer, Indiana University’s main Bloomington campus announced its plan to eliminate more than 100 academic programs. The same moves were then launched at the state’s five satellite institutions as well.

Part of the driver is the concern all parties have regarding university costs relative to the career earnings of a graduate (the average student loan debt for the class of 2024 was $37,850 as of May 2024). Some of the majors being hardest hit are deemed too specialized, or perhaps irrelevant, and have fewer students.

To that end, there’s no question some degrees lead to higher-paying jobs, or more job openings, than others. The good news for the agricultural field is that its university programs are actually faring well amidst the enrollment woes.

Recently retired Purdue Extension Educator Jim Luzar said over his more than 36 years, he’s seen the ebb and flow in terms of college enrollment and majors. Surpluses of graduates in a field will lead to droughts and then shortages, much like anything else that adheres to the classic supply and demand curve taught in Econ 101.

But at present, there’s a huge demand for graduates from agricultural colleges, and he’s excited for the future.

“I see a lot of opportunities for young people. Whether they get a two- or four-year degree,” he said.

Luzar acknowledged that the cost of obtaining a degree these days is a factor in the overall enrollment trends. But, unlike other fields where courses and even majors are being eliminated from the university, ag is seeming to prosper due to real demand. And that demand helps explain the relative stability of agricultural programs and enrollment numbers.

By the numbers

One of the challenges in isolating college enrollment numbers by a particular field is the sheer number of universities. The U.S. boasts roughly 6,000 institutions of higher education between two- and four-year schools and specialty schools. Of those, there are only about 150 with majors in agriculture, 112 of which are land grant universities.

The fact that college agriculture programs aren’t as prolific as the more generalized liberal arts majors does make for a unique look. Historically, majors like “psychology,” “sociology,” and “business administration” lead the pack in gross numbers. But majoring in an ag-related field requires a little more specificity. Most, if not all, students in an undergraduate college of agriculture were specifically guided there either by way of a high school program, 4-H, FFA, or similar mentoring program. (The National FFA Organization even announced in summer 2025 that it again hit record numbers of over 1 million active members.)

One example of a small ebb and flow would be Iowa State University’s College of Agriculture and Life Sciences, As of spring 2025, there were 3,431 total undergraduates in the college, with “animal science” as the top major with 874 students, followed by agriculture studies at 343. In the spring of 2024 there were a total of 3,480 total students, again with 849 in animal science and 328 in agriculture studies. In 2023 there were 3,569 total, with 903 in animal science with 334 in agriculture business.

Yet, when rolling back the clock to spring 2011, there were 3,434 — nearly the same as 2025.

One of the key variables noted across the board is the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic and academic disruption it caused from kindergarten through college. Another data point here that helps explain the ebb and flow would be in the 2025 statistics concerning gender. Of the 3,431 undergraduates, 1,955 were female and only 1,427 were men. In 2011, the men outnumbered women by about 100, and in years prior, the difference was even more stark.

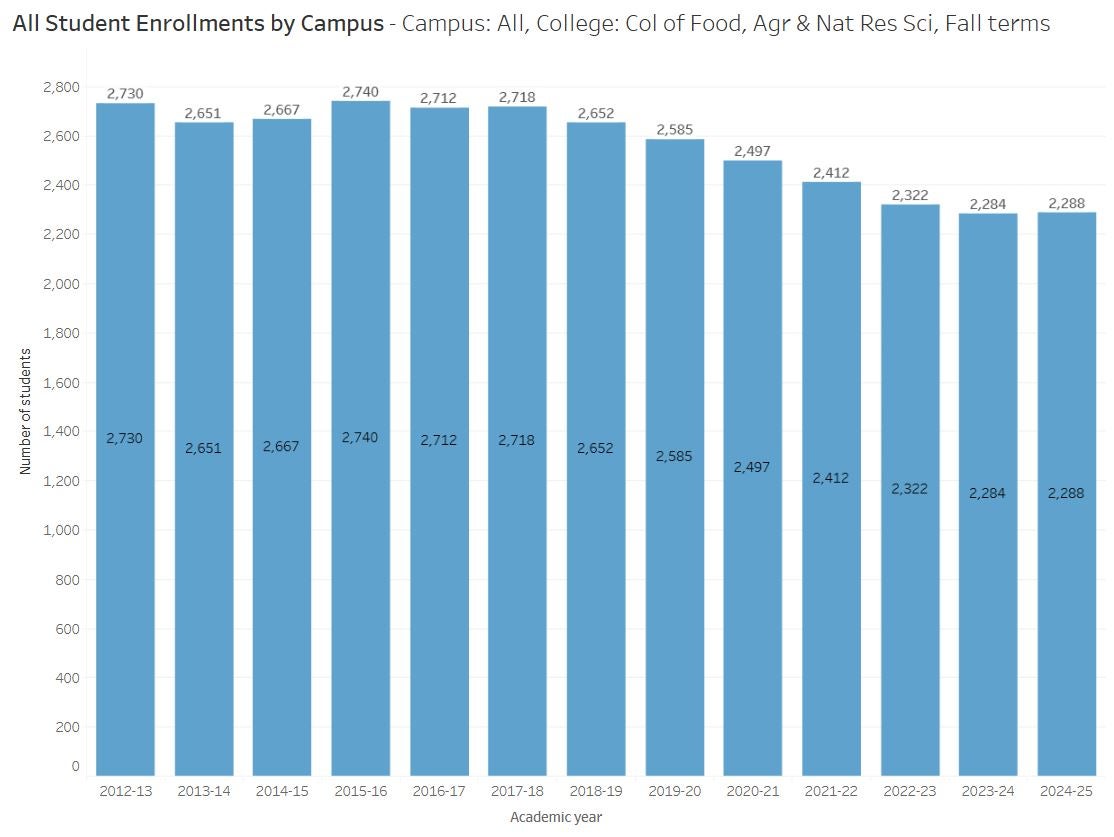

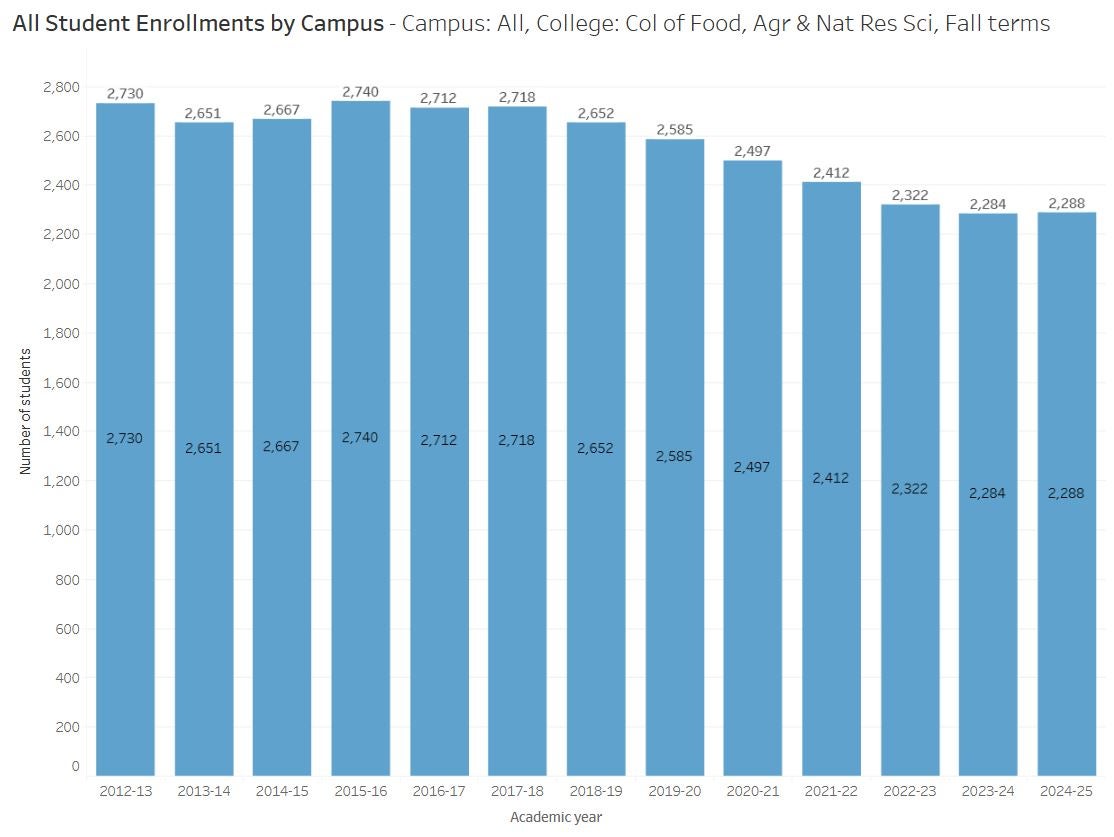

Another example, which shows a bit of a controlled slide, would be the University of Minnesota’s College of Food, Agriculture, and Natural Resource Science.

For the 2024-25 fall term, total enrollment across all campuses for that ag college was 2,288. This is up from 2,284 in 2023-24, and 2,322 in 2022-23.

But consider that in 2012 the same metric was 2,730, and then 2,651 the following year. That equates to a 17.6 percent decline between then and now.

Again, a big part of the overall decline in enrollment is due to fewer men going to college, and more women and international students filling in those roles. According to a Pew Center report, there were 1.2 million fewer 18- to 24-year-olds enrolled in 2022 than 2011, and only 0.2 million of those were female. Today, 42 percent of students at four-year institutions are men, down from 47 percent in 2011. Agriculture programs have historically been more male-dominated, and as women come into those spots, there’s a bit of a slip and slide. The issue is being addressed at the national level by a myriad of groups.

“Our goal with HEMAC [Higher Education Male Achievement Collaborative] is to ensure that every student has the opportunity to thrive, and we firmly believe that we can do more for men without doing less for women and girls,” Richard Reeves, founding president of the American Institute for Boys and Men, told the student publication The College Fix.

University of Minnesota Rochester president Lori Carrell actually reported an unusual spike at her particular campus, with 400 freshmen, up 80 percent from year prior. According to Carrell, the big surge for 2025’s freshmen class was due to several factors, including changes to financial aid programming and the COVID pandemic some years prior.

“Here at UMR in our incoming class, we have 52 percent of our students are students of color or BIPOC students. Nearly as many are first generation, and nearly as many are low income. And these are just the students that we want to recruit. So we’re thrilled with the outcome,” she said.

Neighboring Winona State University President Ken Janz noted in the same interview, though that the surge may not be permanent. “I think we will possibly next year have a little growth. But after that, we’re actually going to hit some pretty steep demographic cliffs, where there’s just going to be a lot less 18-year-olds.”

And of course this helps explain the drive universities have to support immigration. One area where agriculture enrollment is certainly growing is among international students. Purdue University’s 2024 International Enrollment and Statistical Report shows a 5 percent increase in international students in the College of Agriculture over 10 years, and 4 percent over one year. With 124 undergraduates and 343 graduate students, the College of Agriculture also claimed 232 “international scholars” among its ranks, second only within the university to the college of engineering’s 490.

In all fairness, how one tabulates the number of students enrolled will have to differ from school to school. In some universities, veterinary programs are contained within the school of agriculture, while not in others. The same is true with many of the life and environmental sciences.

The sheer number of different “agriculture majors” can be make it difficult to get exact numbers, but one thing is clear, the programs aren’t disappearing the way that they are in many non-agricultural departments.

The job demand is there

Luzar said irrespective of the ebb and flow, there’s no questioning the demand for graduates in the field of agriculture.

“There’s a shortage of ag teachers in Indiana,” he said, referencing the public high schools. Many school corporations are resurrecting ag programs they’d let go in years prior. That said, it takes four years to get a teaching degree, so the shortage today will take time to remedy. “That’s creating a demand for those students at the college level. That’s a good sign. The demand is there.”

And that demand is actually spiking across the country, according to a report issued by the University of Minnesota.

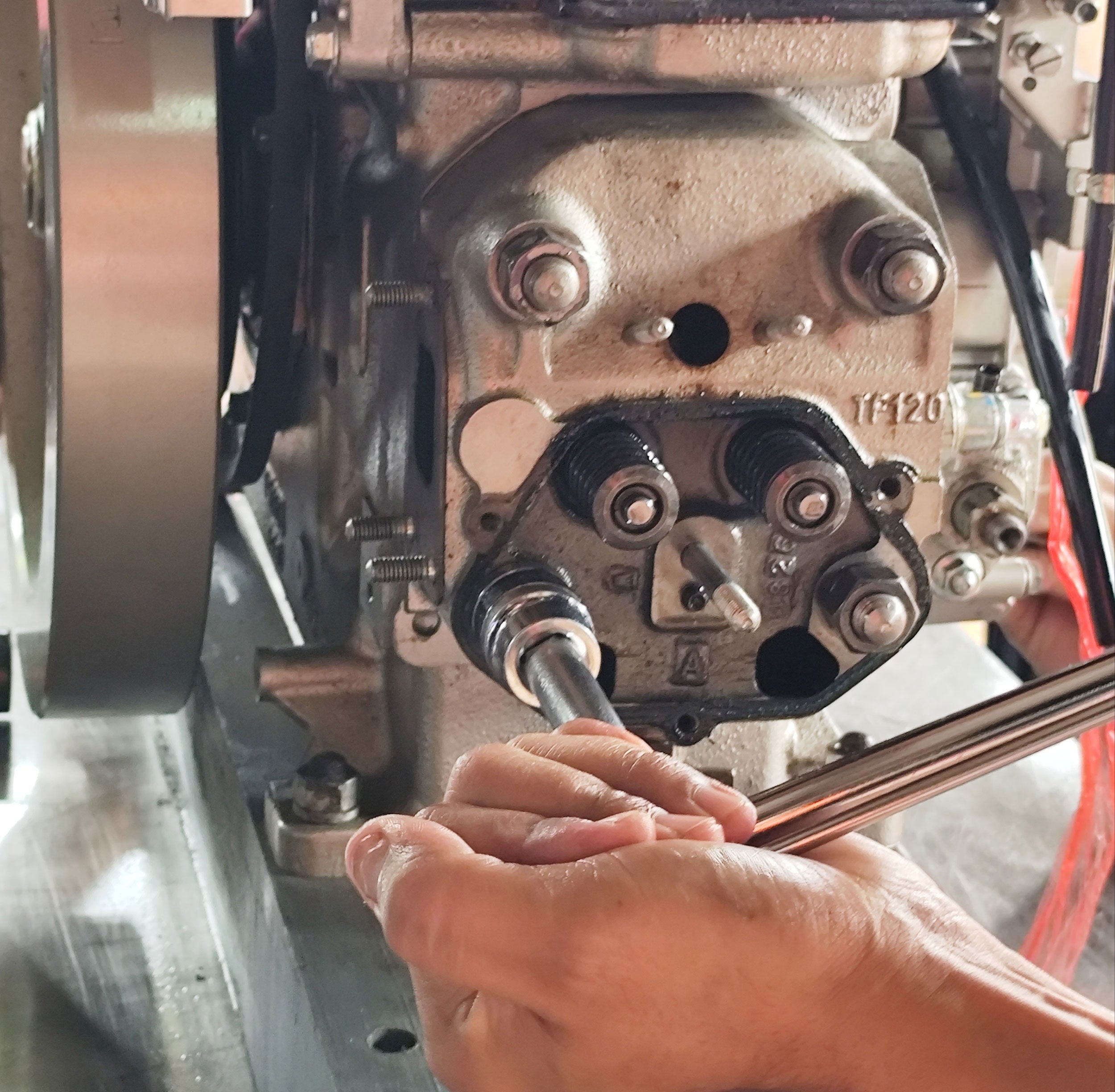

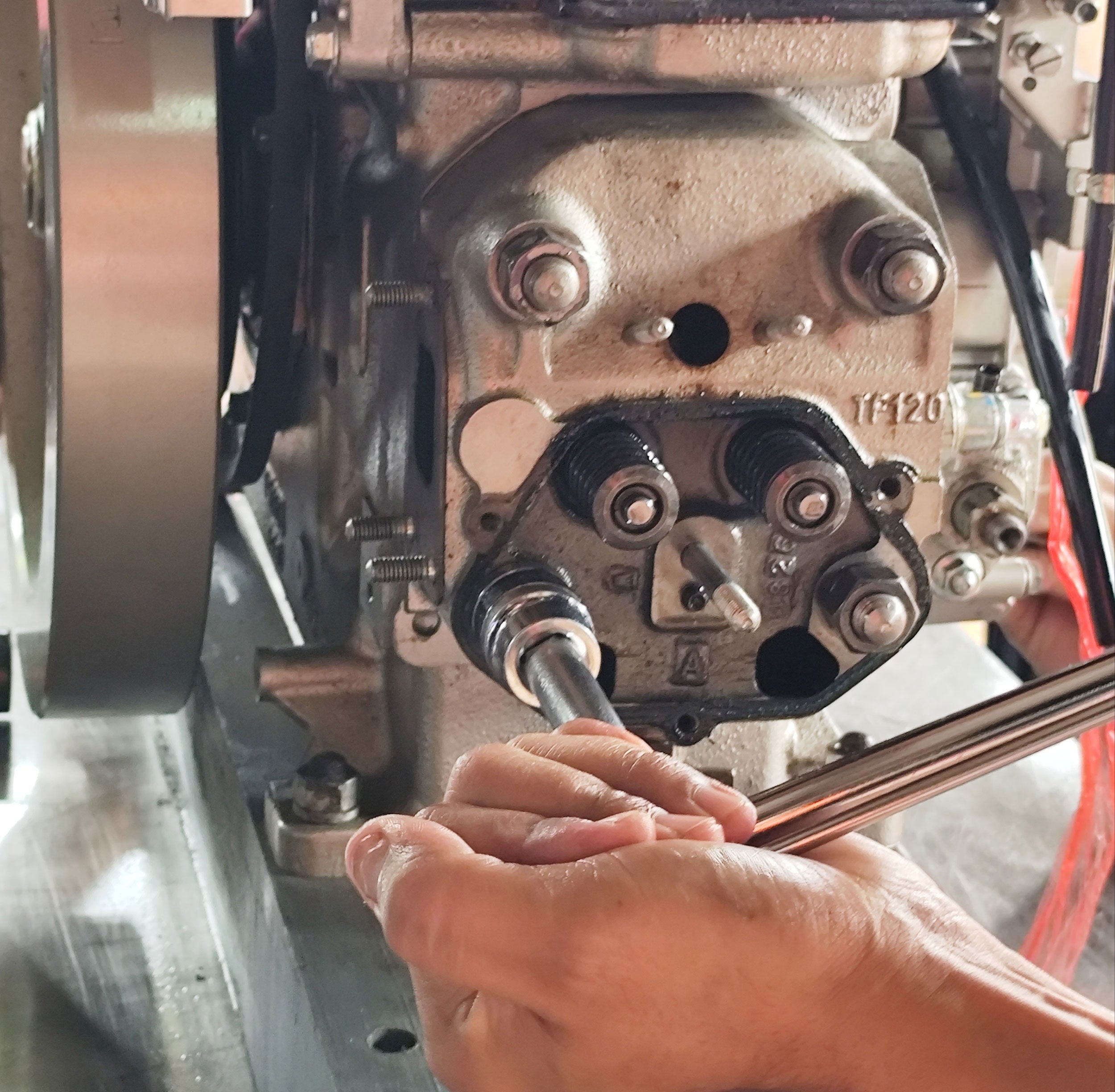

In addition to work as a Purdue Extension Educator, Luzar was also an adjunct faculty member at Ivy Tech Community College in the agriculture technology classes. That program at the Vigo County campus in west-central Indiana is growing for sure, he said.

“There’s so much demand for people who can operate, maintain, and repair equipment. Not just drones, but now the combine and tractor,” he said, noting the modern producer isn’t working with the same equipment as yesteryear. One area producer with 3,000 acres presently employees two 25-year-old graduates to do nothing but technology work.

“Farmers have to have that technology to be competitive,” he said.

And the same demographic shift that is crunching some universities is actually helping college graduates in agriculture as the Baby Boomers get out of the field, both literally and figuratively. This means more information at the K-12 level about the opportunities a university education can provide would be one solution to the problem, along with the continued drive to bring more foreign students in to fill the open spots.

Brian Boyce is an award-winning writer living on a farm in west-central Indiana.