Author Gabriel Rosenberg advocates that the structure of industrial food production and distribution is key to achieving the best nutrition and food security.

Many people squirm when they hear the term “industrial.” It is often used to conjure images of soulessness and greed. And when someone uses the phrase “industrial agriculture,” for example, it’s usually directed in a way that accuses the system of being driven primarily by profit and efficiency rather than stewardship, sustainability, or care.

So, when food-policy experts Jan Dutkiewicz and Gabriel N. Rosenberg make the argument that the American industrial food system is an asset rather than a liability, they stand out in the public discourse.

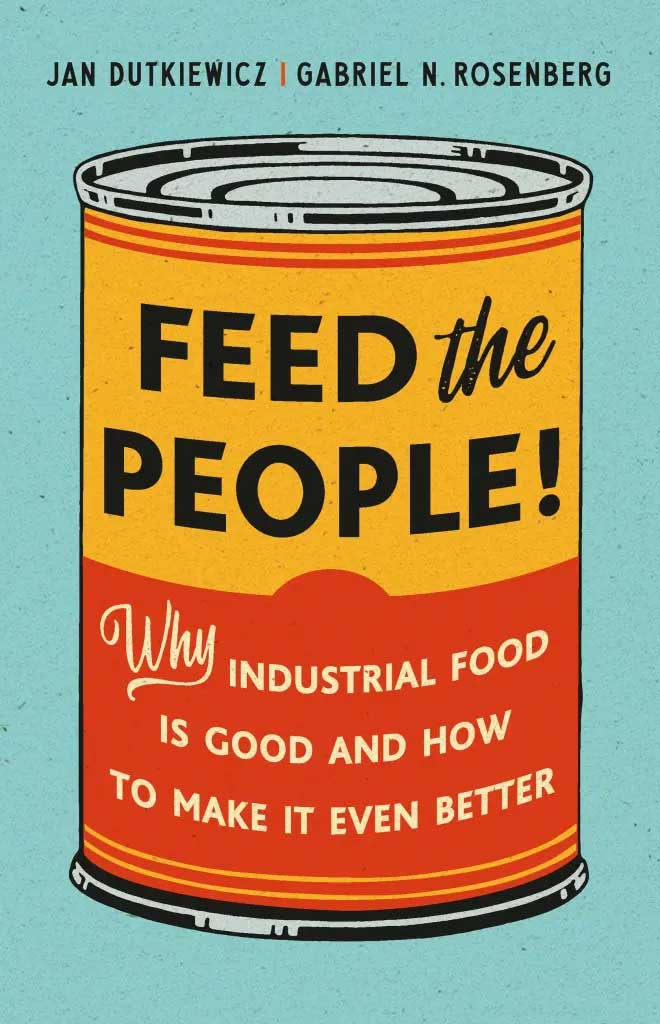

Dutkiewicz, an assistant professor at the Pratt Institute in New York, and Rosenberg, an associate professor at Duke University in North Carolina, have debuted a new book today, Feed the People!: Why Industrial Food is Good and How to Make it Even Better.

Their position is that the current American food system provides more nutritious, varied, fresher, and affordable options than it did a century ago and, perhaps, more so than an at any other time in human history. Their research has led them to show that a nutritionally complete and delicious diet is available at most grocery stores — and that it can be achieved affordably in the form of generic store brands and (gasp!) through the incorporation of some ultraprocessed foods.

They say that too many food writers blame the “industrial” food system for things such as pollution, climate change, and obesity, but Dutkiewicz and Rosenberg don’t believe that the solution, as so many food influencers like to promote, is to buy local, organic, artisanal food from small farmers. Instead, the authors remind the reader that modern technology has made food more affordable, abundant, and varied, and that with the continued application of smart innovations and commonsense policies, society can make them even better.

Rosenberg has previously authored The 4-H Harvest: Sexuality and the State in Rural America, a history of 4-H that considers the relationship of state-building to the emergence of capital intensive agriculture in rural America, while also addressing ideas about family life and gender. Rosenberg has also penned or contributed to dozens of articles for research publications and media outlets, including New Republic magazine and Vox.com.

AGDAILY spent an afternoon chatting with Rosenberg about his latest book and understanding this perspective on the American food process. (This interview has been edited for brevity and clarity.)

AGDAILY: To start, please tell me a little bit of your background and expertise in food policy.

Rosenberg: I’m a Midwesterner, born and bred. From Indiana, and I went to school for my undergraduate degree in Iowa and lived there for a bit afterward. I had a typical Iowa education insofar as I made friends with a lot of people who were from farms, and I got to know the communities around me.

I went to graduate school and had intended to study other things but wound up becoming very interested in rural history and the history of agriculture. The U.S. Department of Agriculture is a major historical object that I’m interested in.

Jan [the book’s co-author] has other forms of expertise, particularly in environmental science, although his Ph.D. is in political science. So, we’re a historian and a political scientist. We write about food, bringing that topic to bear on larger political questions. I think a lot about the policy that informs USDA action and why the USDA does certain things.

One of the more interesting aspects of the book is that, of course, we do talk about the USDA substantially, but we’re also interested in a lot of policy levers that are not part of the USDA. We want to encourage people to think about food politics not exclusively through the farm. Specifically, some of our analysis is that agriculture tends to be one of the most constrained and difficult-to-alter parts of the food system.

That’s a key lesson that we would take from the book: If you want to change the food system broadly, farmers are often the most choice-constricted of the various players. They will say they may not have a lot of agency — if they’re in animal agriculture, they certainly don’t, and if they’re using conventional seeds or they’re involved in commodity agriculture, of course they don’t either. That’s a big point of emphasis, to look at policy mechanisms that are further from the farm. That requires us to think about things like processing and labor and environmental regulation in other parts of the food system.

AGDAILY: Why is the industrial food system — however you choose to define “industrial” — disparaged so much?

Rosenberg: From our perspective, “industrial” is usually defined according to its scalability and the standardization of both the inputs and outputs. We might also call it the conventional food system. It’s the food system that is produced by conventional means rather than the sort of set of alternative means that we would usually characterize as natural, organic, local, and regenerative — which of course all have various meanings that are contested and not always shared by people who are describing it in those terms.

From an agricultural perspective, “industrial” has to do with how food is produced. But the industrial food system is also most grocery stores, most restaurants, and for better or for worse, it’s most of the products that Americans eat. In the last quarter century, despite the greater emphasis on local food, the American food system has grown less local. In other words, we’re more likely to eat food that was produced far away.

With the industrial system, we call attention specifically to the values of standards and scalability.

We think that it’s important that people be able to rely on food and a standard of quality and that everyone has access to it. While there may be really good solutions for cooking things, for preparing things, and for growing things, they have to be able to work for the 300 million people who live in the United States. They can’t just be things that work at a small scale. That’s what we mean by the industrial system. It’s the approaches to food system problems that scale and offer food abundance to everybody.

AGDAILY: You mentioned organic and regenerative, and there are questions in the ag community about whether they’re as scalable as some of the other food-system possibilities. So, does organic production and regenerative or some of the other food and production labels have a valuable role in our modern food system, or are they diverting resources that could be better used elsewhere?

Rosenberg: To be honest, it really depends on the practice that we’re talking about. There may be certain practices that fit within a broader model of regenerative agriculture that should be widely adopted. There are things as simple as something like crop rotation, for example, which are understood to be part of a package of practices that people call regenerative. So, maybe we do want to adopt those. The problem is that regenerative, because it doesn’t have an agreed upon definition, encompasses a wide variety of different practices, many of which are in fact, in tension with each other, and they can’t all be done.

I think that there’s too much of an emphasis on these overarching, almost ideological, commitments rather than being practical and asking, “What’s actually going to get the outcome we want?” For example, if you’re concerned about artificial chemicals getting onto food or concerned about pesticide runoff creating problems for drinking water, one

way is to say it is that we shouldn’t use pesticides. OK, that might be the organic approach, to not use synthetic pesticides. Yet another way would be to say that we ought to be doing more with precision agriculture to decrease the total amount of pesticides used.

And in fact, per calorie and per acre, we now use vastly fewer inputs today than we did in 1970. We use less synthetic fertilizers, less pesticides, less herbicides as well. That’s all for the better. That’s an instance of the industrial food system in some ways becoming less polluting and much more environmentally sustainable.

I don’t necessarily think that the rise of organic alternatives is responsible for that. What’s responsible for that is better understanding of how one controls and uses those inputs. So, that’s using technology in a conventional system — doing more of that as well as using better seed technology that’s more blight resistant or resistant to pests. That to me has a lot more upside to actually reduce chemical inputs than saying, “Oh, we’re going to just do away with synthetics.” I don’t think that’s realistic for most farmers.

It’s a lot easier to plug in these kinds of improvements that fit the model that most farmers already use than it is to start from scratch using much more complex — and sometimes too complex — regenerative or organic or any of these other kinds of buzzwords. Because, what’s more, when those alternatives are used to produce food, they tend to be extraordinarily costly, which means that the most food-insecure people who have the least resources to be able to feed themselves are the ones who are least able to access them.

We are interested in helping those people as well, and we think that that ought to be at the heart of agricultural policy as well as the political ambitions of anybody who wants to get involved in food politics.

AGDAILY: As an observer, do you find it frustrating, if that’s the right word, that these input innovations and seed technologies and other biotech are so focused only on the commodity crops? Obviously, that’s where the larger-scale money is, and we’re not able to get these innovations, like a more blight resistant lettuce variety, as easily in the specialty food sector.

Rosenberg: Absolutely, it’s very frustrating. We have written about Rainbow Papaya, which more or less saved the Hawaiian papaya crop. We need things like gene editing, which is reducing a lot of the underlying costs associated with the modification of a genome.

The problem, of course, is that we haven’t mapped the genomes of a lot of plant varieties that are not commodity crops. We know a ton about the soybean genome, we’ve mapped corn, but what do we know about the cherry? What do we know about the sorrel? Vastly less. And as a result, the underlying basic science that’s necessary to be able to move forward with relatively cheap gene-editing technology is simply lacking.

There are a lot of reasons for that. One is that seed companies are likely risk averse to produce consumable, genetically modified organisms because of how much scare-mongering has gone into what are absolutely safe-to-eat products.

That’s why, in the United States, we do a tremendous amount of GMO agriculture here, but it mostly goes into things that humans don’t directly eat — it goes into animal feed and it goes into ethanol and maybe it gets into the corn syrup.

People are being told to fear “Franken Foods,” and they’re being told to fear these things that we have 50 years’ worth of solid data on saying that these are in fact safe. They do not pose a hazard. They have a major upside.

Government can step in to correct that market failure, through, for example, something like a national laboratory for food science and technology, which we currently lack. That seems to us to have enormous upside when we consider how science and technology have improved agriculture in the past century.

AGDAILY: How far away do you think we are from turning the tide of public opinion on foods edited with CRISPR or with lab-grown meats, which still have pushback?

Rosenberg: I’ve had the lab grown meat — I’ve had the fish, I’ve had pork, I’ve had chicken. And they do taste legit. On the front of whether companies can produce foods that are delicious and nutritionally identical to meat from animals, they’ve succeeded at that. But the economics are pretty daunting, in part because of public resistance that we’ve mentioned. They’re also daunting because there are real engineering and scientific challenges, and there is very little in the form of public resources available to help meet those challenges.

For example, something as basic as bioreactor design. We need much, much better bioreactors, particularly large-scale bioreactors, for commercially viable cultured meat. I’m a techno optimist, and I want to tell you that those things are right around the corner, but I’m not sure I can tell you that.

AGDAILY: What I’m seeing is the marketing side, the influencer side, which tends to be almost exclusively against it. And recently a South Dakota lawmaker introduced a bill to ban lab grown meat for the next 10 years. We don’t know if things like that will actually go anywhere, but those are appear to be some of the biggest obstacles.

Rosenberg: I think so too. There is certainly resistance to development. But before we can even talk about that aspect, there’s the question of whether consumers will eat it.

That’s one issue I don’t particularly want to prognosticate on. The limited data we have, which comes from Singapore, are that if you offer it to consumers and they eat it, they actually like it. It really quickly breaks down resistance.

Yet even that is separate from the issue of whether they can be commercially viable.

AGDAILY: How is what we’re eating today different compared to what our parents or our grandparents were encountering on the grocery store shelves?

Rosenberg: It’s probably not that different from what your parents were seeing. Ultra-processing today may involve more novel forms of processing, and a Double Stuf Oreo may now be ultra-processed in a way that it wasn’t 50 years ago, but a Double Stuf Oreo was bad before we invented the concept of ultra-processing and before the underlying techniques that are used to do ultra-processing were invented.

The really interesting question is if we go with the Michael Pollan guidance, right? And Pollan’s famous advice is that you’re not supposed to eat anything that your great-great-grandmother wouldn’t recognize as food. That sounds really good until you realize that 100 to 150 years ago, before the advent of the industrial food system, 100,000 people died of pellagra, which is an easily prevented niacin deficiency. We had rickets, we had marasmus. Many people don’t even know what marasmus is, since it doesn’t exist anymore because it was eliminated by enrichment.

What was available for people to eat was also radically different in some pretty simple ways. Food was more likely to be contaminated, it was more likely to be spoiled, and the variety of fresh produce — the thing that everyone is supposed to be getting more of, according to virtually all nutritional science — was simply unavailable to the overwhelming majority of the population for the entirety of the year.

One of the things that I would say was the biggest historical change is that there is more produce available, it’s more delicious, it has greater variety than at any other time in American history and arguably in human history. That’s a really good thing.

And the thing that I would emphasize about these good options is that they are overwhelmingly produced by conventional production methods and conventional processing. They are industrial foods. Almost everything in your supermarket is.

There is a healthy, nutritious diet available at your local supermarket, you just have to find it.

AGDAILY: What’s your take on the newly released Dietary Guidelines? They really lambaste processing and ultra-processing, which many would argue is vital for food deserts and low-income, busier people these days.

Rosenberg: The reality is that many ultra-processed foods are calorically dense and engineered to be hyper-palatable so that they are addictively snackable, which makes it easier for people to overindulge. Though that’s not true of all ultra-processed foods. And so that category frequently catches a bunch of things that are perfectly safe to have in your diet.

We are able to distinguish in a number of peer-reviewed studies that it depends on what the underlying food is that’s being processed more so than the level of processing.

So, what is the real problem? Our dietary science, from 1971 until very recently, tended to say that Americans ate too much protein, didn’t eat enough fresh fruit and vegetables, and ate overall too many calories. Besides the encouragement of people to eat more red meat and dairy, the new guidelines don’t make a substantial departure from prior guidelines, which I think is actually kind of like the untold story and is very interesting. But the imperative finally to eat “real” food, which is the rhetoric associated with it, I really worry is going to misguide people. I worry that it’s going to make people say that the only food that I can eat is this real boutique stuff.

And what will wind up happening is that because the boutique fruits and vegetables are more expensive, most people are just going to eat red meat now. That seems like a very, very bad outcome from the perspective of most nutritionists and most nutritional science.

AGDAILY: As a general advocate for the industrial food system, you’ve explained where the good is, such as the accessibility of fruits across the whole country and being able to have year-round access to different kind of foods. So, what parts of this system need to be improved?

Rosenberg: We take the position in the book that more vigorous enforcement of antitrust laws would benefit markets for both commodities and inputs — and certainly within animal agriculture too, with the domination of five firms.

And which politicians do farmers usually support? They support politicians that don’t tend to do very much about antitrust issues.

Elsewhere in the food system, we also want to gesture back to this problem of looking off the farm to other places where there’s a lot of room for improvement. Millions of people work in food, whether in a customer-facing position like your server at a restaurant, or a truck driver, or somebody who works in processing plant, or even the cashier at a gas station. Many of these jobs are among the worst-compensated and most dangerous in the United States.

I would encourage people to go and listen to Waffle House employees — Waffle House in my opinion has some of the worst-reported workplace conditions out there. Listen to what these employees say when they’re doing a unionization drive: They don’t want Waffle Houses closed, they want them improved. These millions and millions of workers who should be paid better and who should have better working conditions do not want their industrial jobs eliminated; they want to be paid fairly and treated well, and we should support them in their effort to do so.

That, to me, is a core part of improving the food system that’s often neglected when we think about boutique alternatives. Workers are not looking to flee the industrial food system — they’re trying to make it better again and again. That’s the kind of the approach that we want to emphasize.

There’s a huge portion of Americans who are food insecure, and that means that they don’t have the income to purchase the food that they and their families need. That to me is a scandal, and it’s also a scandal that we have policy solutions for it that are relatively straightforward but not employed — the direct distribution of food and income to those people is the most efficient way to deal with food insecurity.

There are many community benefits to things like gardens and farmer’s markets — those are all lovely things — but they’re not efficient ways to feed or people. SNAP, universal school lunches, those are efficient. Those are existing programs that are underfunded and that are being cut further, and that rely largely on the conventional industrial food system. They try to harness it to feed people. So, rather than spending all of that money on building a bunch of gardens that are really low yield and that aren’t creating food options in the middle of winter, we give people an ATM card to go and buy their food.

These solutions, though, require us to engage the industrial food system, not to dismiss it.

Ryan Tipps is the founder and managing editor of AGDAILY. The Indiana native has a master’s degree in Agriculture and Life Sciences from Virginia Tech and has covered the food and farming industries at the state and national levels since 2011.