At dawn, the first thing most farmers do is open a gate. It’s a simple act. An act that makes way for possibility. Cattle move to fresh pasture. Tractors roll toward the field. Hands and technology meet to start another day’s work.

But in agriculture’s newest frontiers — automation, sensors, and artificial intelligence — too many gates remain closed. Not to the land this time, but to opportunity.

When we talk about the future of farming, we talk about technology, such as the sensors in the soil, drones in the sky, or data in the cloud. Agriculture is evolving faster than ever, but the question we need to be asking is: Who is getting to shape that future, and who is being left behind?

From GPS guided tractors to AI driven crop management, the demand for technical expertise in agriculture has outpaced our pipeline of skilled, diverse workers. Apprenticeships and workforce programs designed to prepare the next generation of ag tech leaders are booming. Yet for too many students of color, especially Black students, access to those programs remains an uphill climb.

In recent years, national and state data have revealed a pattern that mirrors what we’ve seen for decades in traditional agricultural education: underrepresentation.

While students of color make up a growing share of the high school population, they remain significantly underrepresented in advanced technical and STEM related agricultural pathways. Even my home state, California, has its own data that shows that Black students comprise just over 5 percent of total secondary enrollment, but less than 3 percent of participants in agriculture, natural resources, and engineering related programs.

That pattern extends to apprenticeships and internships that serve as the launching pads for high skill agricultural careers.

And this isn’t about ability or interest; it’s about access. Many of the same barriers that have long shaped inequitable educational outcomes continue to echo through the ag tech landscape: under-resourced schools, lack of culturally responsive mentorship, and the persistent absence of representation in leadership roles.

My recent research into student leadership programs and career technical organizations found a clear correlation: students who felt a sense of belonging and representation were more likely to persist to graduation and pursue further technical education. When students, particularly Black students, saw leaders who looked like them and felt affirmed in their identity, their engagement deepened. Yet those inclusive spaces are still the exception, not the norm.

That same dynamic applies to apprenticeships. In 2024, a joint report from the Association for Career and Technical Education (ACTE) and U.S. Department of Labor data, Black or African American apprentices remain significantly underrepresented in registered apprenticeship programs overall. Even among programs emphasizing high tech skills, precision agriculture, automation, data analytics, participation by underrepresented groups remains stagnant.

These numbers aren’t just statistics; they represent lost innovation, unrealized potential, and an agricultural workforce that risks becoming less reflective of the nation it serves.

Consider the growth of youth apprenticeship programs in ag tech sectors. Across the country, partnerships between universities, private companies, and state agencies have launched “next gen” initiatives to connect students with emerging careers. Yet many of these opportunities exist primarily in suburban or rural districts with already strong CTE infrastructure. In urban or historically underserved communities, the programs are often underfunded or absent altogether. Students who might excel in these fields never even hear about them.

It’s a paradox: The industry calls for innovation, but the systems meant to cultivate it often replicate old exclusions.

This divide isn’t inevitable; it’s structural. Research on career and technical education has long shown that when programs intentionally integrate equity and cultural relevance, outcomes improve across the board. Schools that embed mentorship, representation, and belonging into their CTE and co-curricular programs report stronger persistence and completion rates, particularly among students of color. In the data, those interventions translate into higher graduation rates, greater career confidence, and deeper civic engagement.

One promising model is equity centered apprenticeship design, programs that combine technical skill development with culturally responsive mentorship and wrap around support. Pilot programs that align agricultural technology apprenticeships with organizations like Minorities in Agriculture, Natural Resources, and Related Sciences (MANNRS) have begun to close participation gaps. By centering belonging, these programs do more than teach students how to operate new tools; they teach them that they belong in the rooms where agricultural innovation happens.

But the real opportunity lies in how educational and industry leaders respond. The federal Perkins V legislation requires states to report disaggregated CTE data and develop plans to close access gaps. Yet too few programs use that data to reshape recruitment, mentorship, and representation strategies.

Equity audits shouldn’t be a compliance checkbox. They should be the blueprint for change.

Apprenticeships that diversify agriculture’s workforce don’t just advance social justice, they advance resilience. Agriculture thrives on diversity: of crops, of soil microbiomes, and of people. When only a narrow slice of the population builds and manages the technology driving the industry forward, we lose perspectives essential to solving the next generation of challenges, from climate change to food insecurity to ethical AI.

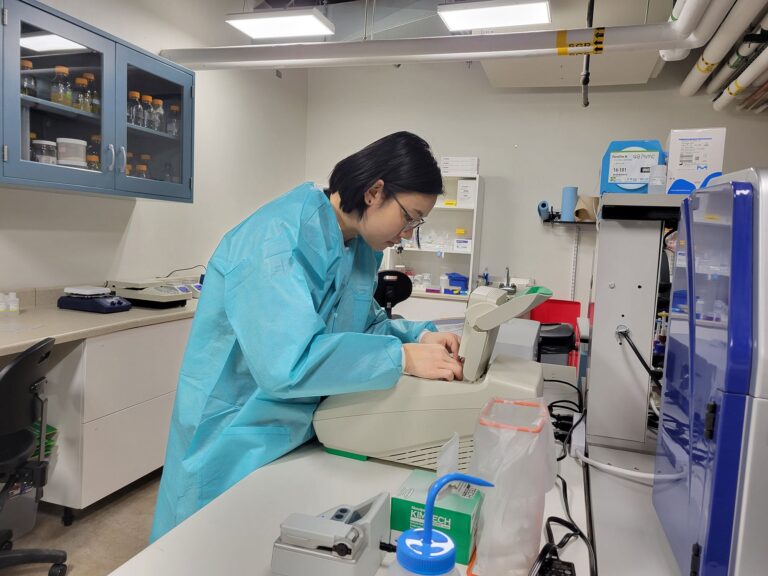

For decades, diversity initiatives in agriculture have focused on the field. Now, they must also focus on the lab, the data center, and the innovation hub. Because as agriculture becomes increasingly digitized, equity must evolve alongside it.

The next generation of agricultural professionals will write code, pilot drones, and analyze data sets alongside tending crops or designing irrigation systems. If we want that generation to reflect the richness of our agricultural communities, then we must design systems that don’t just welcome diversity. That means reimagining how we recruit, mentor, and retain talent across the agricultural workforce. It means investing in educators and CTSO advisors who understand how culture, belonging, and leadership intersect. It means expanding scholarships, removing participation fees, and ensuring that a student’s zip code doesn’t determine their access to the future of farming.

Agriculture has always been about stewardship of land, of people, and of potential. As technology reshapes the landscape, our responsibility expands. The question is no longer just who grows our food, but who gets to grow with the industry.

Because the future of agriculture isn’t just automated. It’s human. And inclusion must be part of its operating system.

Bre Holbert is a past National FFA President and studied agriculture science and education at California State-Chico. “Two ears to listen is better than one mouth to speak. Two ears allow us to affirm more people, rather than letting our mouth loose to damage people’s story by speaking on behalf of others.”