As farmers face historic headwinds and market hardships, calls to the national Farm Aid hotline and the Iowa Concern hotline — where farmers can get support in times of mental health crisis or need — are increasing.

This fall the Iowa Concern hotline saw four to five times the number of calls it had in the same months last year, said Tammy Jacobs, the hotline’s manager.

The Farm Aid hotline is also seeing a change in the urgency of calls.

“We’re seeing more established farmers calling in — people who know how to play the game and how to access programs. They’re calling more often now, because even with all that institutional knowledge, they’re still running into issues for the first time that are more complex and difficult to solve,” said Lori Mercer, a Farm Aid hotline operator. “The system that’s in place is simply letting them down. There’s just no further safety net.”

Research shows farmers die by suicide at least twice as often as people in the general population, so there’s urgency to address the uptick in need.

“It’s a huge issue. I mean, we’ve known at least three families this year whose loved ones died by suicide,” said Emma Yerkey, who’s part of the Ag Chapter of Gray Matters, a monthly meetup for ag producers around the Quad Cities to talk about their struggles.

Farmers experience a lot of stressors and uncertainty that they can’t control — isolation, weather changes, and financial pressures — along with low access to mental health care in rural areas and stigma that may make them keep their pain to themselves. Market conditions made worse by a trade war and inflation are adding to the stress. Mental health professionals are thinking outside the box to get producers care.

Understanding the stress

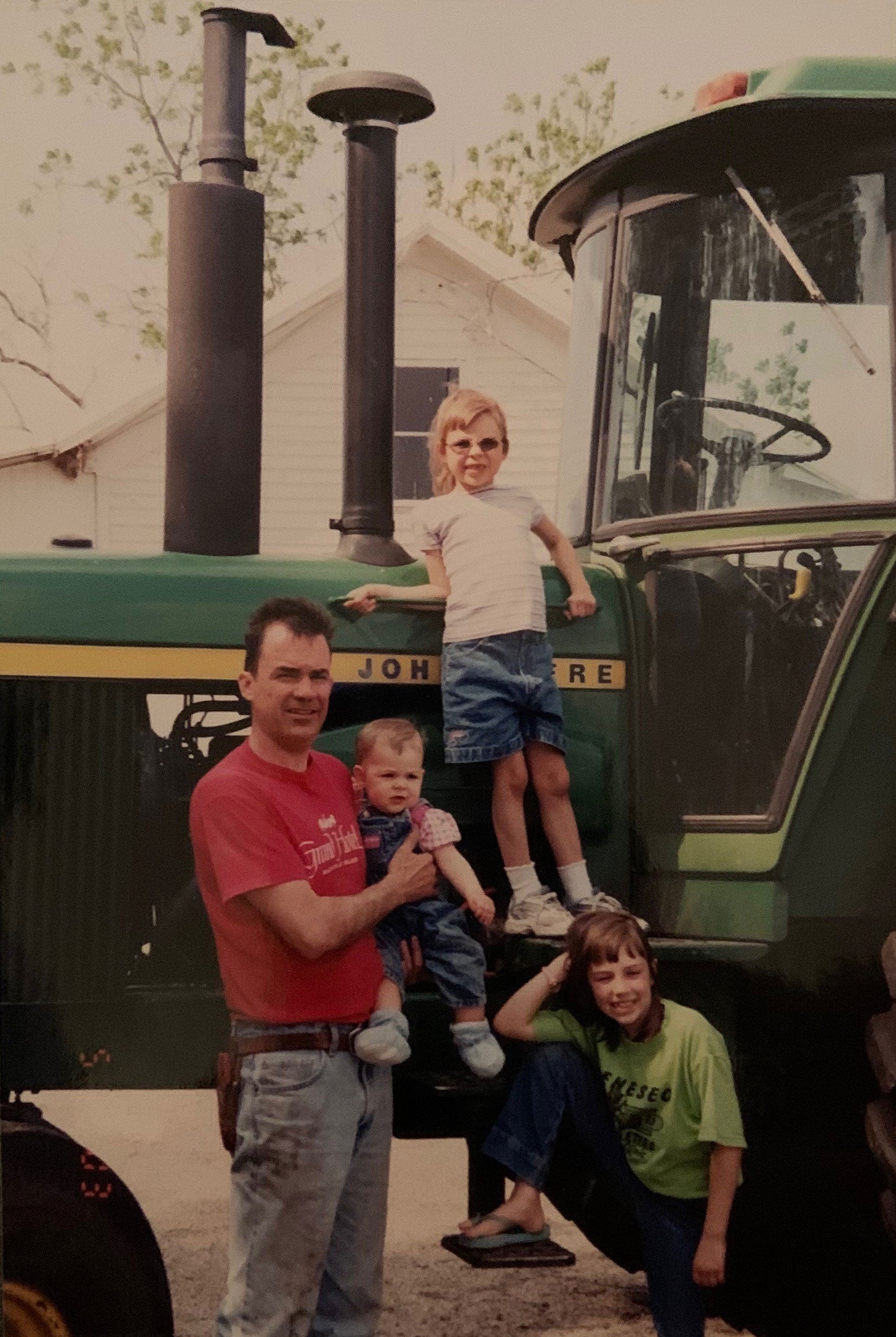

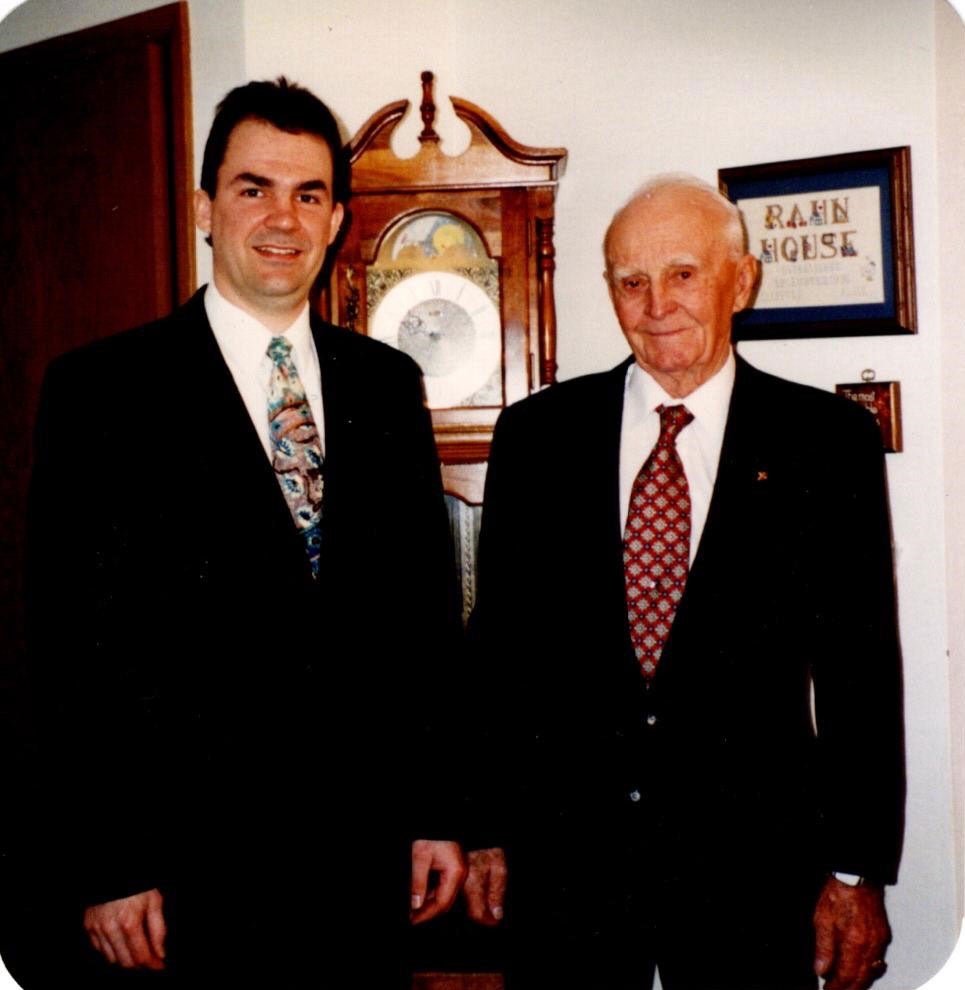

Yerkey’s family farms corn, soybeans, and hay in Geneseo, Illinois, on land they’ve owned since the Civil War. The farm is filled with memories, especially of her dad, Tim Yerkey.

She played baseball with him in their driveway, the family ate meals together in the home, and, one year, her father helped her raise a ribbon-winning calf.

“That was a really good memory that I have with him,” said Yerkey.

But the farm could be stressful, too. Tim Yerkey worked the land with his family, but at times had to take outside jobs to make ends meet. In 2011, he’d been struggling for about a year when spring floods left fields underwater. He’d reached out to friends and visited the emergency room seeking help, only to be told there were no beds, Yerkey said. He died by suicide in June 2011.

“I miss my dad, and I don’t want anybody else — or any other family — to go through that,” Yerkey said.

But many farming families experience similar pain. Between 2003 and 2017, more than 1600 farmers died by suicide, the majority older white men.

Experts say factors that contribute to stress and higher suicide rates among farmers include isolation, easy access to guns, a cultural expectation of toughness, stigma around seeking mental health care, worries about who will take over the farm, and a lack of recognition for their hard work.

Financial losses and stress are also significant risks for depressive symptoms. And right now, times are tough for farmers.

Producers have endured high inflation and growing input costs on farms since at least 2020. The spread of COVID and, more recently, policy decisions like President Trump’s tariffs and increases in immigration enforcement have all increased operating costs. At the same time, prices for major commodities are low — lower than the cost to grow them. Corn prices are about $0.85 below the break even point and soybeans are about $2 below.

This year, many states are expecting a record corn crop, but farmers aren’t celebrating.

“It’s very discouraging for farmers to think that they’ve done all the things right in their fields and have put innovations in place and made good decisions, but yet, even with strong yields, they’re gonna be facing a loss on what they’re producing,” said Aaron Lehman, president of the Iowa Farmers Union.

In 2024, the U.S. exported about 42 percent of its soybeans, most of it to China. With China not buying in the midst of the trade war some farmers who usually send their crop abroad have struggled to find new markets. The U.S. in November struck a new deal with China, potentially extending a lifeline to producers still scrambling to move their harvest, but it remains to be seen what China will actually buy.

Some programs that helped connect farmers to domestic markets, like the Local Food Purchase Assistance initiative, have also been cut by the USDA.

“Since the beginning of the year, the farmers have just been thrown into a different level of uncertainty with policy things like losing access to some markets through tariffs, losing access to staff and programming with the government shutdown, and the funding freezes. A big one we’re hearing about is losing access to labor with the ICE raids, etcetera,” said Mercer, with Farm Aid. “I was just speaking to a farmer the other day who was basically watching his crops rot on the vines because his usual labor support was just too afraid to show up this year.”

In addition to all of the financial stress, farmers say they feel the work can be thankless.

“This work is incredibly hard, and nobody understands where their food comes from. Nobody knows that [farmers] work 20 hours a day so that they can have a strawberry,” said Anna Scheyett, a retired professor of social work who studied farmer stress and suicide at the University of Georgia.

Meeting farmers where they’re at

Despite the many struggles, some families are finding hope and community in turbulent times. To honor her dad, Yerkey joined the new Ag Chapter of Gray Matters, a Quad Cities nonprofit that provides mental health resources, education, and safe spaces

Gray Matters hosts monthly Barn Talks, where participants can share what’s weighing on them, whether it’s stress, depression, anxiety, or other struggles, and receive support from others. The organizers hope to build a sense of community and normalize talking about mental health.

“Feeling comfortable and safe to say that — ‘Hey, I am stressed out, or I am really hurting right now. Maybe I am depressed, maybe I have some anxiety,’ — whatever it might be,” said Heather Gritton, one of the group leaders.

Offering spaces where farmers can meet and take some of that load off their shoulders can help break down the stigma around getting help, said Sara Kohlbeck, assistant professor of psychiatry and behavioral medicine at the Medical College of Wisconsin.

It’s key for those spaces to be easily accessible to farmers.

“Bringing that support to the farmers — or to the rural communities — rather than expecting those folks to come and get those resources for themselves is really important,” said Kohlbeck. “Otherwise, you know, we’ve got folks that are kind of suffering in silence because they just don’t have the time. Sometimes there’s stigma, and there’s kind of that pride issue.”

There are also practical barriers. Telehealth isn’t a viable option for many farmers, as cell and internet reception in rural areas are limited. Driving long distances to see a counselor can also be impractical, especially during the busy harvest season.

Another approach to reaching farmers has been to train people who farmers trust and regularly interact with — such as suppliers, lenders, large animal veterinarians, and spouses — to recognize when someone may be dealing with mental health challenges and teach them how to support them and direct them to resources.

For example, Scheyett has trained agricultural lenders to recognize warning signs of suicide ideation and taught them how to respond. She’s also trained extension agents to take a few minutes at the beginning of agricultural production meetings to talk about stress and offer resources, something she says can make a real difference for farmers.

In one study, Scheyett and her co-authors found that farmers who were present at meetings where about 10 minutes were dedicated to talking about stress management walked away with new ideas for managing stress and a higher level of commitment to doing it.

Sometimes, offering practical and logistical solutions to big problems can be a part of mental health services, too.

“If a farmer has not really looked and done a deep dive into their farm financial system, we have a program that’s called farm financial associates, and they’ll come out to the farm, do a big evaluation over the farming operation to see where the hard points are and is there a way to switch things around, diversify, in order to help offset some of the farming losses and costs,” Jacobs, with the Iowa Concern hotline, said.

For farmers facing grain storage challenges, Jacobs suggested partnering with other farmers as an alternative to traditional co-op arrangements.

Scheyett suggests everybody can help by thanking farmers the same way we do with the military.

“Every time I see a farmer, I say thank you — thank you for your service, because what you do keeps us healthy, fed, and clothed,” said Scheyett.

It’s all in the hopes of providing care and saving lives.

“Even if you can save one life, I mean, that’s so worth it,” said Yerkey. “I feel very passionate about it.”

Farmers can reach out to the 988 Lifeline or 1-800-FARM-AID for help. Help is also available in Spanish.

The Iowa Concern hotline is available 24/7 via chat, email, call, or text at 800-447-1985.

This story is a product of the Mississippi River Basin Ag & Water Desk, an independent reporting network based at the University of Missouri in partnership with Report for America, with major funding from the Walton Family Foundation.