With a $1 million Agriculture and Food Research Initiative grant from U.S. Department of Agriculture’s National Institute of Food and Agriculture, Iowa State University scientists and collaborators are leveraging the Swine Disease Reporting System to rapidly detect new strains of porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus.

They have launched a one-of-a-kind web-based tool called the SDRS BLAST Tool (BLAST stands for Basic Local Alignment Search Tool) that allows veterinarians, producers, and other users to compare genetic sequences of PRRSV with those in the Swine Disease Reporting System.

South Dakota State University, the University of Minnesota, Kansas State University, Ohio Animal Disease and Diagnostic Laboratory, and Purdue University are collaborating on the project.

“For the first time in the swine industry, we can use private data, while keeping providers anonymous, to generate information and share it with stakeholders who can use it in the decision-making process to manage and control an economically important disease such as PRRSV,” said Dr. Giovani Trevisan, research assistant professor at Iowa State. “Therefore, the platform has the potential to rapidly inform U.S. citizens about health challenges affecting swine farms, which is critical for the sustainability and secure pork supply.”

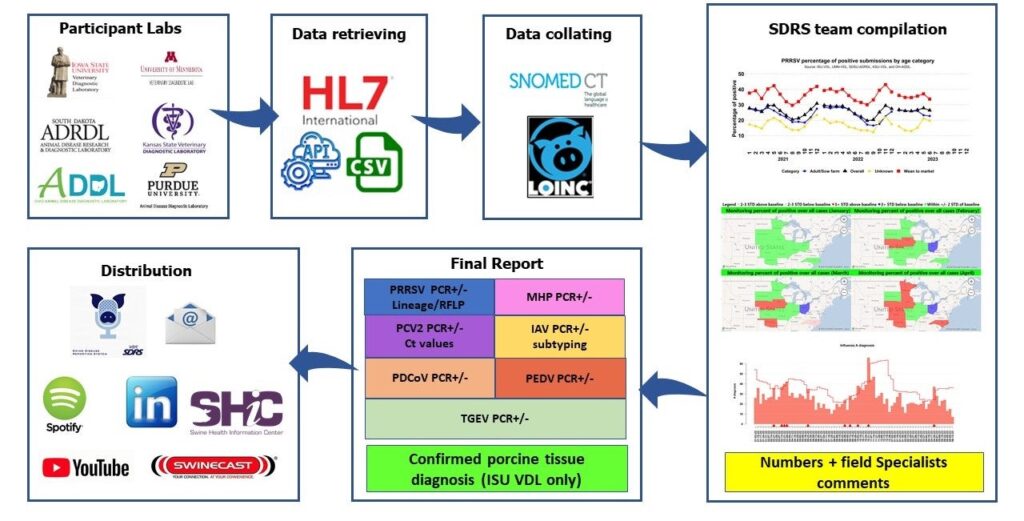

The Swine Disease Reporting System is a strategic collaboration between six National Animal Health Laboratory Network-accredited veterinary diagnostic labs, universities and key industry stakeholders. The system collects, collates and monitors diagnostic data of nine infectious agents in U.S. swine herds while keeping farm, producer, production system, veterinarian and participant laboratory confidential.

PRRSV is a devastating endemic disease. A 2013 study estimated the total cost of productivity losses due to PRRSV in the U.S. national breeding and growing pig herd at $664 million annually. Recently, more aggressive PRRSV strains have emerged, potentially increasing the economic burden of this pathogen due to increased mortality rates in the farms.

“Collaboration with industry stakeholders is critical to a timely disease response, and this project, in part through the SDRS Blast Tool, is building relationships needed on a day-to-day basis for endemic disease management,” said Dr. Michelle Colby, national program leader for animal biosecurity at NIFA. “Relationships that will be essential if we are ever faced with the need to respond to a transboundary or emerging disease within the U.S. swine industry.”

Using retrospective data, the SDRS detected 133 new PRRSV sequences from 2010 to 2023. The majority of the new strains were detected in samples collected in Iowa, Minnesota, Indiana and Illinois. Most of these new sequences were detected in grow-finish pigs, which highlights the importance of this age group on the ecology of PRRSV and likely other pathogens, requiring efforts to improve biosecurity and biocontainment and thus mitigating the risk of the emergence of new strains.

Additionally, the SDRS team has been tracking the geographical spread of a very aggressive PRRSV strain named L1C.5. The L1C.5 emerged in 2020 in Minnesota, posing a devastating threat to affected breeding herds. Breeding herds that were naïve to PRRSV went up to 10 weeks without any piglet production due to the devastating impact of this PRRSV strain.

At the end of February 2024, when the SDRS PRRSV Blast tool had just been released, an L1C.5 PRRSV was detected in South Carolina for the first time. The detection of an L1C.5 PRRSV in South Carolina poses an imminent threat to the largest U.S. swine breeding inventory located in North Carolina, where this strain has never been seen before.

In addition, the SDRS Blast Tool helped identify that the South Carolina PRRSV sequences had a 100% match with other sequences seen in other states that were not South Carolina’s neighboring states.

Researchers said the BLAST Tool has the flexibility to be adapted to receive sequences from other pathogens like African Swine Fever which is a transboundary animal disease. In the event of a detection of ASF in the United States and if permitted by USDA, the participant labs could send the generated ASF sequences on a real-time basis to the SDRS to keep track of pathogen spread and genetic evolution.

“Providing epidemiological information to decision-makers can help in the decision-making process of disease prevention and control, safeguarding pork production and food security,”