DAILY Bites

-

Researchers at UW-Madison and the Morgridge Institute successfully developed pig retinal organoids, finding they share similarities with human retinal organoids, making pigs a valuable model for testing ocular therapeutics.

-

By leveraging single-cell RNA sequencing and immunocytochemistry, scientists identified key genetic and cellular similarities between pig and human photoreceptors, advancing the potential for stem cell-based vision restoration.

-

The study, funded by the U.S. Department of Defense, aims to explore cell replacement therapy for retinal injuries common in the military, with ongoing pig transplants to assess the integration of lab-grown photoreceptors.

DAILY Discussion

Inside the human eye, the retina is made up of several types of cells, including the light-sensing photoreceptors that initiate the cascade of events that lead to vision. Damage to the photoreceptors, either through degenerative disease or injury, leads to permanent vision impairment or blindness.

David Gamm, director of UW — Madison’s McPherson Eye Research Institute and professor of ophthalmology and visual sciences, says that stem cell replacement therapy using lab-grown photoreceptors is a promising strategy to combat retinal disease. The challenge is that stem cell treatments aimed at replacing photoreceptors need to first be tested in animals. Since human cells are not compatible in other species and are quickly rejected when transplanted, it’s difficult to assess their potential.

“Pig and human retinas share many key features, making pigs ideal for modeling human retinal disease and testing ocular therapeutics,” Gamm says. “By testing ‘human-equivalent’ photoreceptors in pigs, we can get a better sense of what these cells can do if they are not immediately attacked by the host animal.”

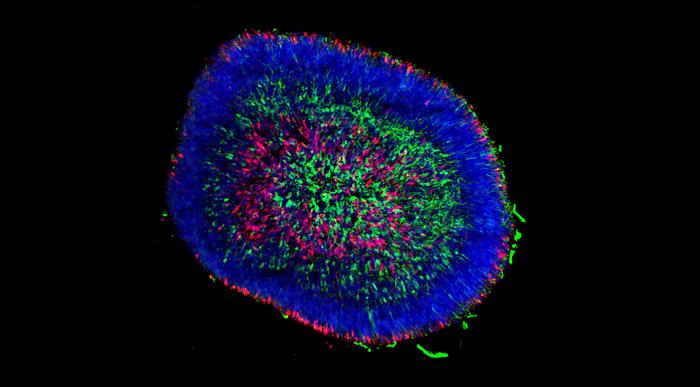

In a new study published in Stem Cell Reports, the Gamm Lab partnered with researchers at the Morgridge Institute for Research to develop lab-grown pig retinal organoids. They found that pig-derived photoreceptors shared many similarities with those made from human retinal organoids.

“This is the first time that people have made pig retinal organoids,” says Kim Edwards, a graduate student in the Gamm Lab and first author of the study. “And this was the first time that people have done a comparison of human versus another species of retinal organoids.”

Organoids are small tissue clusters — about the size of a large pin head — made up of hundreds of thousands of cells, which allow scientists to replicate the cellular interactions and conditions in a human tissue or organ, but in the controlled environment of a lab dish.

“The photoreceptor cells within human organoids can respond to light and communicate with each other through synaptic connections,” says Gamm. “To determine whether they can connect inside a damaged retina and restore vision, we need to transplant and test them in pigs.”

Edwards says that to get quality organoids, it’s important to start with quality stem cells. They collaborated with University of Calgary assistant professor Li-Fang “Jack” Chu, formerly a postdoc in Jamie Thomson’s lab at the Morgridge Institute, to obtain the pig pluripotent stem cells.

“Historically, the Thomson Lab has been good at making human induced pluripotent stem cells,” says Ron Stewart, Morgridge investigator in computational biology. “But it turns out that making them for additional species like pig is really challenging. Jack worked it out and is leading the way with his new lab.”

After successfully generating pig induced pluripotent stem cells, the next challenge was to encourage them to differentiate into retinal cells. Edwards began by using the Gamm Lab’s established human organoid protocol to see if it would work using stem cells from pig. The protocol timing was based on the human gestation period of 40 weeks, but they noted a pig’s pregnancy is only about half that length. So, the scientists thought, what if we use the same protocol, but cut the timing in half?

“We were able to make a lot of retinal organoids from that, which was really exciting,” Edwards says. “It’s a good proof of concept to show that if we’re going to differentiate to a specific cell type, we really need to pay attention to the gestational differences and the inherent differences between the cells.”

Using immunocytochemistry techniques, they characterized proteins associated with specific retinal cells present at early-stage versus late-stage development in both pig and human organoid models. To dig deeper, the Gamm Lab collaborated with computational biologist Beth Moore in the Stewart Computational Biology Group at Morgridge to look at gene expression within the cells using single-cell RNA sequencing (RNA-seq).

“They did a lot of magic using single-cell RNA-seq — things that we didn’t even think were possible,” Edwards says.

The organoids are dissociated into individual cells, and each cell is tagged with a barcode and sequenced individually. The data captured is then used to group similar cells together, giving in-depth insight into the nature of all the cell types found in the organoid, including rod and cone photoreceptors and other cell types such as retinal ganglion cells.

“It’s an unbiased and very comprehensive view of what genes are expressed in each cell type in the organoid,” says Moore. “It’s a different type of marker from the immunochemistry. It’s a different way to come to the same conclusion of identifying different cell types.”

Both Edwards and Moore had to overcome challenges to arrive at these conclusions. First, given the nature of organoids, Edwards needed to optimize their protocols to separate the cells and maintain them prior to sequencing.

“They don’t like to be dissociated and put on a dish, especially the photoreceptors,” says Edwards. “We joke that the photoreceptors work better together, just like people.”

On the data analysis side, Moore explains that each cell gets encapsulated in a droplet that contains the barcode for sequencing. But sometimes, one droplet encapsulates multiple cells, or the droplet might be empty and not contain any cell, which introduces errors in the sequencing data.

“That can really mess up your analysis, especially when you are trying to identify different cell types,” Moore says. Moore developed an analysis pipeline to filter out any unwanted sequences and normalize the data. She then mapped the genes expressed in different clusters, which they could map to specific cell types and compare with the immunocytochemistry results.

Another challenge — the significant difference between pig and human genomes — meant Moore also had to work through a list of known genes in both species and match them with the sequences to map out the different cell types.

“Having that confirmatory data from Beth was really critical for us to feel confident about what we were seeing,” Edwards says.

This work was supported by a grant from the U.S. Department of Defense in collaboration with the National Eye Institute with the aims of exploring cell replacement therapy to treat retinal injuries that commonly occur in the military. The researchers have begun to do transplants in pigs using photoreceptors from the pig organoids to determine whether they establish connections and make synapses with downstream neurons.

“We’re excited to show that you can grow these retinal organoids from different species and that a lot of groups across the world are starting to make them,” says Edwards. “It all starts from having good stem cells.”

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc()/6895915516_c5d91051e4_o-dcfd56ad94744fe7a21a73a4193bf43a.jpg)

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc()/BloombergContributor-2213407471-950399016ccb4e73ab5886ad1d623b2e.jpg)

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc()/For-Sale-Farmland-Natalina-Sents-Bausch-d53037fe10b24b288740b5a3089aa5c7.jpg)

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc()/adm-1-ee7f0c8ca6d74828a32b170d601c90c5.jpg)