The United States’ approach to global food security, along with its leadership in animal public health, changed course on President Donald Trump’s first day in office with a 90-day pause on foreign aid programs.

Heading into the new administration, budget cuts and efforts to improve the “efficiency” of government programs were expected. However, recent executive orders are already having unexpected impacts on agriculture, land-grant universities, and international agricultural partnerships working to improve health outcomes.

Since 1954, the United States has provided funding and led projects in numerous diplomatic missions to combat global hunger, partnering with philanthropic organizations and fostering public-private partnerships to address global challenges.

Those involved in international agriculture and food development are scrambling for answers in Washington as federal agencies suspend operations, issue termination notices, and prevent employees from reporting to work at the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID).

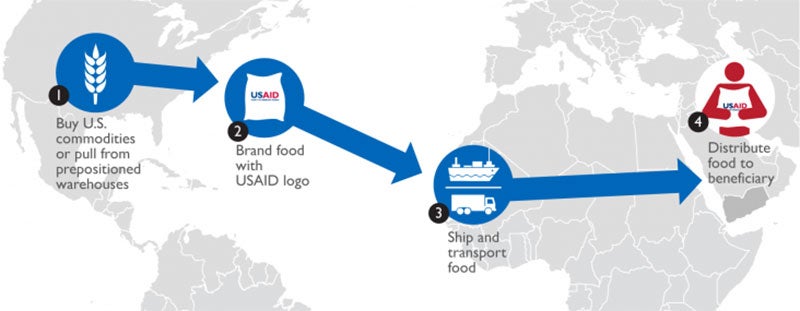

In 2023, USAID disbursed over $72 billion in aid to approximately 130 countries. Notably, $2 billion of that is used to purchase U.S. commodities for processing into meal sent overseas, serving an estimated 45 million beneficiaries, one Foreign Agriculture Service report said.

The last time the agriculture community had intensive discussion about food aid was during the introduction of the American Farmers Feed the World Act of 2023, which worked to ensure 50 percent of food aid programs utilized U.S.-grown commodities, in addition to U.S. shipping requirements set out in the farm bill.

The fight for American farmers who feed the world, and their global development counterparts, are struggling to determine the next steps as long-supported programs are placed on temporary hold and USAID dismisses key personnel and seemingly shutters USAID operations.

Now, a couple of weeks into Trump’s presidency, USAID and U.S. State Department officials are searching for clarity. The global development community is struggling to determine its role as the administration freezes foreign aid, dismisses key personnel, and seemingly shutters USAID operations.

A 90-day pause has been imposed on new foreign assistance obligations and disbursements while all foreign aid programs undergo review. The Office of Management and Budget (OMB) has issued an order to “stop, cease and/or suspend any work” performed under USAID funding agreements.

Among the affected programs are USAID-funded Feed the Future labs, which focus on global hunger and food security across 12 land-grant universities. However, information about Feed the Future has disappeared from public websites. The University of California, Davis, for example, hosts three of the 22 Feed the Future labs, specializing in horticulture, food safety, and market resilience. Other schools involved included Kansas State University, Michigan State University, Purdue University, and Virginia Tech.

The administration has made the decision to re-evaluate U.S. foreign aid by stating that “the foreign aid industry and bureaucracy are not aligned with American interests and, in many cases, are antithetical to American values.”

Mark Becker, president of the Association of Public and Land-grant Universities, criticized the White House’s directive saying, “Ordering a temporary pause of federal grants is an overly broad mandate that is unnecessary and damaging.”

Secretary of State Mark Rubio recently assumed leadership of the agency, though uncertainty remains as Congress debates the issue on whether he can do that. Meanwhile, the State Department has yet to appoint a special envoy for global food security — a role previously held by Dr. Cary Fowler, who had strong ties to the agriculture sector and organizations such as the World Food Prize Foundation and U.S. Farm Foundation. This position represents the U.S. in global food security discussions.

Trump also announced his intent for the U.S. withdrawal from the World Health Organization, a move he pursued during his first term. The withdrawal process requires a one-year notice, but it remains unclear whether Congress will allow it to proceed.

In the agricultural sector, the WHO collaborates with the World Organization for Animal Health to coordinate responses to zoonotic diseases such as African swine fever and avian influenza. While both organizations receive U.S. funding, WOAH funding is expected to continue, with implementation led by the USDA’s Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service.

Animal health experts argue that the United States’ withdrawal from the WHO does not directly compromise animal health but rather “excludes the U.S. from key discussions and collaborations,” according to an international animal health official. “It’s a role the private sector can step into,” this official added. The WHO, WOAH, and the Food and Agriculture Organization collaborate on global animal-human disease interfaces, One Health initiatives, and weekly reports.

Trump’s retreat from global public health commitments comes as avian flu continues to spread. The U.S. has already recorded 67 outbreaks, including one confirmed human case (the patient died last month). In Europe, a case was recently confirmed in the United Kingdom. Agencies worldwide are ramping up surveillance and response protocols.

Avian influenza, a disease that spreads between wild birds and livestock, has been documented since the early 20th century, when it was known as “fowl plague.” However, its resurgence in the U.S. in 2022 posed a significantly greater risk due to the industrial scale of American poultry farms, where individual operations often house more than 75,000 birds. These large facilities, which produce 95 percent of the nation’s eggs, according to the U.S. Poultry Industry Manual, create conditions that can accelerate the spread of disease. In contrast, poultry farms in the Global South typically maintain much smaller flocks, averaging 10 to 23 birds, while the average U.S. backyard flock consists of around 49 birds, one National Institutes of Health study reported.

A Long Island duck farmer recently suffered an outbreak that required culling 10,000 birds. The operation told reporters with NBC, “If duck farming isn’t an option, I’m not sure what we’d do,” a farmer said. “We’re not really set up for anything else.”

When animal diseases disrupt markets, governments often take swift action to mitigate economic damage.

Germany recently faced a foot-and-mouth disease outbreak, prompting a temporary halt in meat exports and the WOAH suspending its FMD-free status. Trade restrictions followed from Korea, the UK, the U.S., Russia, and Japan, though some have been lifted. German Member of the European Parliament Norbert Lins urged economic aid for farmers, who lost an estimated €1 billion.

“Many farms are unable to deliver animals and are experiencing losses of €60,000 to €80,000 per day for months,” he said. “If you do the math, we should be thinking about compensation — that’s only right.”

Governments worldwide have intensified responses to animal disease outbreaks due to their significant economic impact. Under the previous USDA administration, actions such as enhanced testing, financial assistance programs, and indemnity payment programs were implemented to support farmers affected by animal disease outbreaks.

The USDA’s response to animal disease has remained consistent through the presidential transition. U.S. Agriculture Secretary nominee Brooke Rollins stated during her Senate confirmation hearing, “I know that the current team and the future team will be working hand-in-hand to do everything we can on animal disease.”

However, during that hearing, Sen. Amy Klobuchar (D-Minn.) questioned Rollins about “halting external public health communications from the CDC on these avian flu outbreaks.” Specifically, she raised concerns about the Center for Disease Control and Prevention’s Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, which now requires approval from a political appointee before release.

Klobuchar urged Rollins her to discuss the issue with the CDC saying, “I know that wasn’t under the USDA, I just urge you to talk to them about that. We’re concerned.”

Jake Zajkowski is a freelance agriculture journalist covering farm policy, global food systems and the rural Midwest. Raised on vegetable farms in northern Ohio, he now studies at Cornell University.