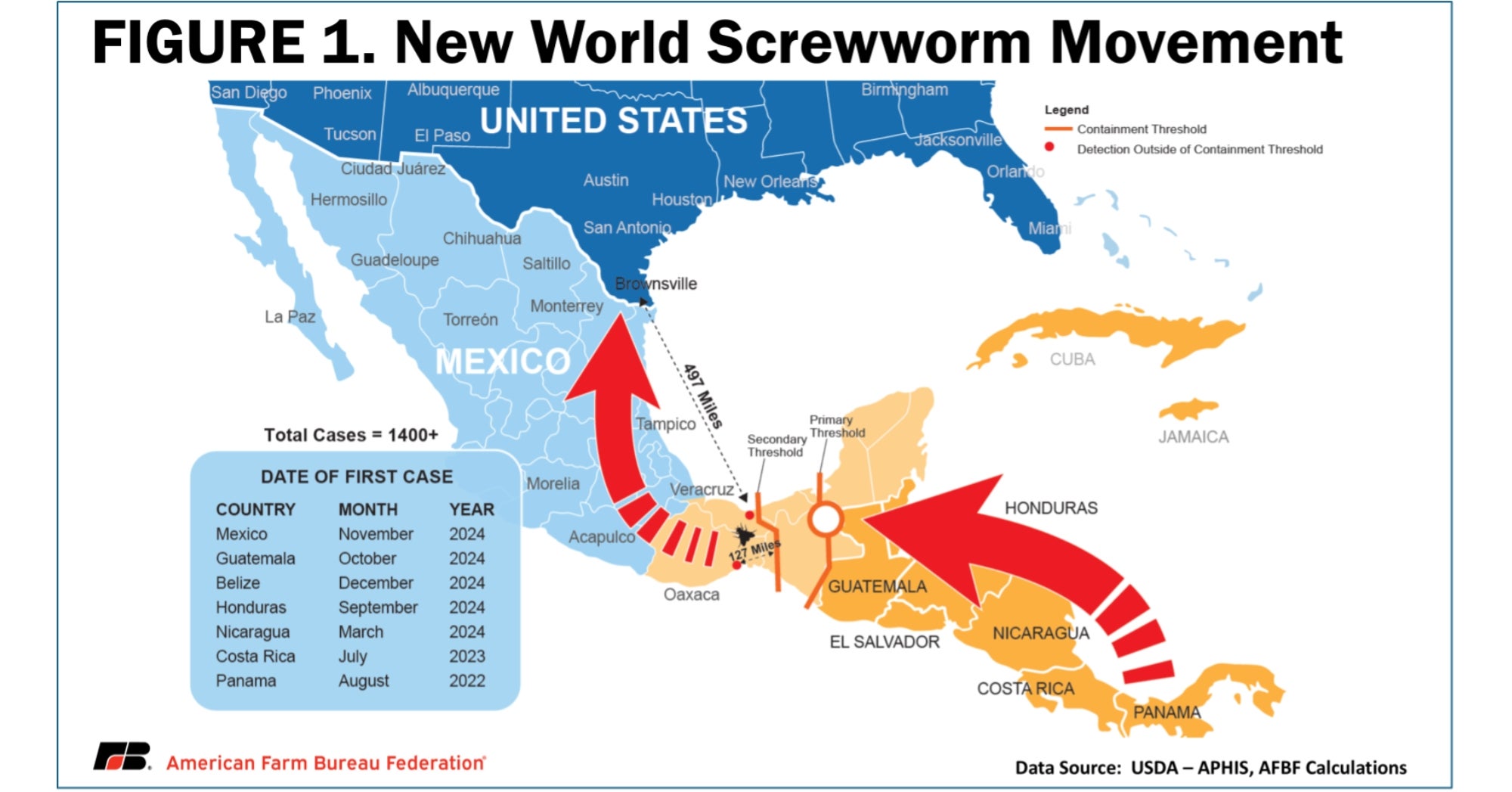

The growing outbreak of New World screwworm in Mexico has triggered serious concerns for U.S. agriculture. First detected in Chiapas in November 2024, NWS has now breached containment thresholds, spreading more than 127 miles beyond the secondary buffer zone into Oaxaca and Veracruz.

With over 1,400 detections in Mexico, U.S. Agriculture Secretary Brooke Rollins suspended live animal imports from Mexico on May 11, citing insufficient sterile fly capacity to contain the spread.

Sterile Insect Technique, which involves releasing sterile flies to control wild screwworm populations, has been the primary tool in keeping the pest at bay. The Panama facility currently produces 100 million sterile flies per week, but with the outbreak advancing north, this is no longer enough to maintain the biological barrier between Mexico and the U.S.

The economic implications are staggering. According to U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Economic Research Service, a screwworm outbreak in Texas alone could cost $1.9 billion annually. Texas, home to 12.5 million cattle, holds 14 percent of the U.S. herd — double that of any other state. These estimates are based on data from the 1976 outbreak, adjusted for today’s labor shortages and cattle inventory.

On the ground, NWS infestations are costly and deadly. Treatment requires veterinary intervention, medication, and added labor. Infected animals often lose weight or die, and mother cows may be unable to care for calves, further increasing operational burdens. Ranchers may need more horses for inspection and handling — animals that are also vulnerable to NWS.

With containment broken and sterile fly production at capacity, urgent investment in expanded facilities is needed. But even then, rebuilding control will take years. The NWS threat now ranks among the top animal health concerns in 2025, and the window to prevent its spread into the U.S. is rapidly closing.