The United States has confirmed its first human case of the New World screwworm, a flesh-eating parasite that has alarmed public health and livestock officials as it advances northward through Central America and Mexico. The case, confirmed by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the Maryland Department of Health on August 4, involved a Maryland resident who had recently traveled to El Salvador.

A spokesperson for the Department of Health and Human Services, Andrew Nixon, told NPR that “this is the first human case of travel-associated New World screwworm myiasis (parasitic infestation of fly larvae) from an outbreak-affected country identified in the United States.” He added that “currently, the risk to public health in the United States from this introduction is very low.”

The Maryland Department of Health said the patient has since recovered, and there is “no indication of transmission to any other individuals or animals,” NBC News reported. David McAllister, a spokesperson for the department, called the case a “timely reminder for health care providers, livestock owners and others to maintain vigilance through routine monitoring.”

New World screwworms (Cochliomyia hominivorax) are parasitic flies that lay eggs in the wounds or natural cavities of warm-blooded animals. When the larvae hatch, they burrow into living flesh in a screw-like motion, sometimes spreading infection or even killing the host if left untreated.

The parasite poses a far greater threat to livestock than people. Outbreaks in Central America and southern Mexico have devastated cattle herds in recent years, forcing the U.S. Department of Agriculture to suspend cattle imports from Mexico multiple times since late 2024. The U.S. Department of Agriculture estimates suggest an outbreak in Texas alone could cost $1.8 billion in livestock deaths, labor costs, and treatment expenses.

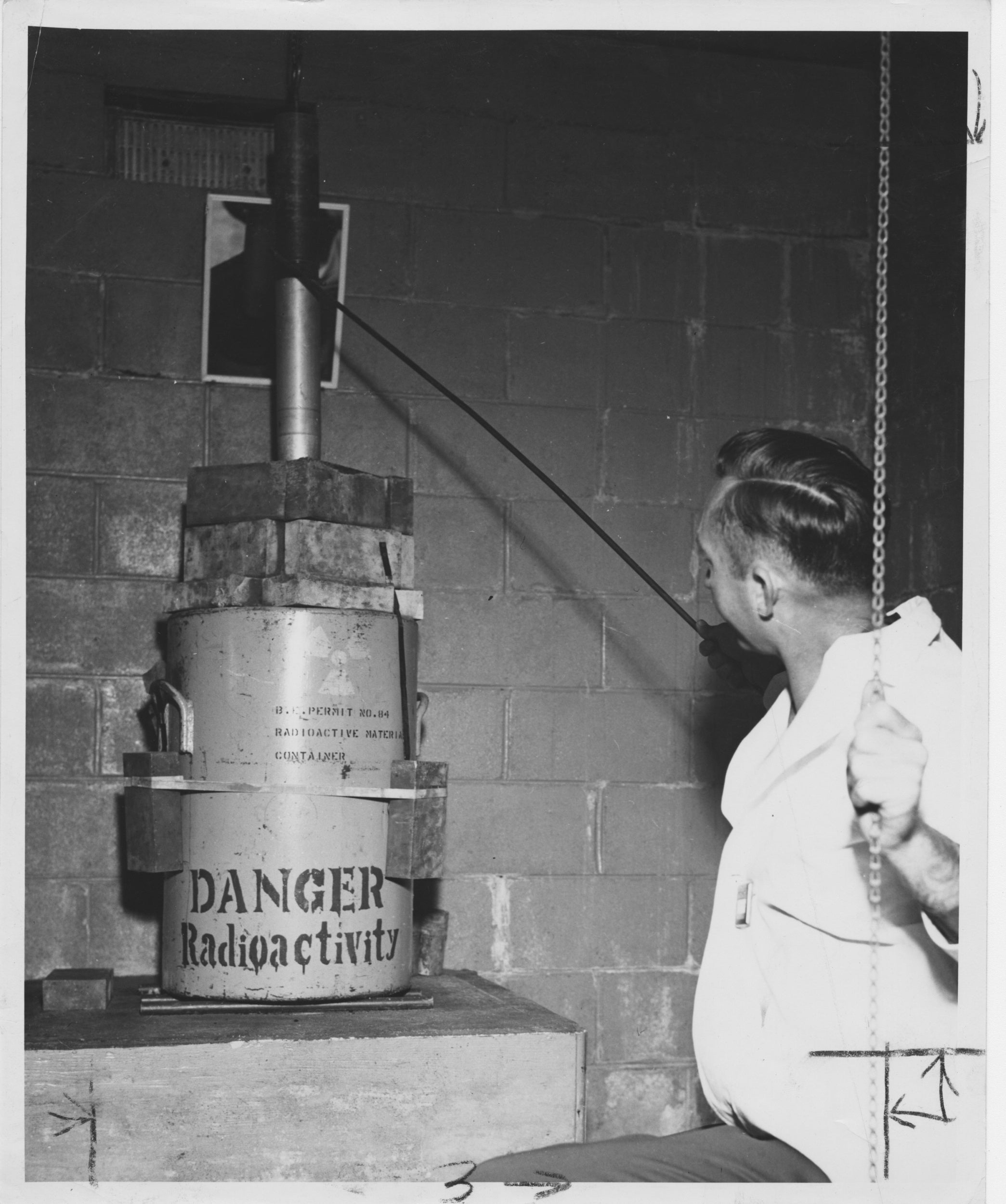

The U.S. eradicated screwworm in the late 1900s using the sterile insect technique, releasing mass-reared male flies sterilized with radiation to disrupt reproduction. Agriculture Secretary Brooke Rollins announced earlier this month that USDA will build a new sterile fly production facility at an air base in Edinburg, Texas, capable of producing 300 million sterile flies per week.

“It took decades to eradicate this parasite from within and adjacent to our borders more than a generation ago, and this is a proactive first step,” American Farm Bureau Federation president Zippy Duvall said in a statement.

But some industry leaders say the government has not moved quickly enough. Reuters reported that state veterinarians learned of the Maryland human case informally before CDC publicly confirmed it, leading to criticism of the agency’s transparency. Beth Thompson, South Dakota’s state veterinarian, told the outlet, “We found out via other routes and then had to go to CDC to tell us what was going on. They weren’t forthcoming at all.”

The screwworm’s northward march has intensified fears in the cattle industry, which is already strained by record-high beef prices and the smallest U.S. herd size in seven decades, and border ports closed.

For now, federal health officials stress that the risk to the general public remains low. But as CNN noted, the outbreak spreading across Central America since 2023 has already reached southern Mexico, just hundreds of miles from the U.S. border. With human and livestock health on the line, authorities are racing to rebuild eradication infrastructure before the parasite makes landfall inside U.S. herds.