Farmers are being forced to adapt to the effects of climate disruptions on their crops’ valuable water resources.

The recent millennia of climate stability are rapidly eroding, and farmers who rely on the hydrological cycle to nourish their crops are poised to feel a disproportionate impact from increasing climate disruptions.

For decades, the gap between agricultural water use and the annual supply of water resources has been widening, with Food and Agriculture Organization data showing that about 70 percent of freshwater consumption around the world happens in the agricultural sector.

Experts are recognizing that this shift is causing less reliable precipitation, rising temperatures because of carbon dioxide and water vapors being trapped in the atmosphere, and a change in the availability of both surface and groundwater used for irrigation — all of which is putting agriculture on the front lines of this crisis.

The expectations because of this change will be dramatic sways in water availability, soil fertility loss, and pest infestations in crops.

The signs are stark and significant, and they’re happening globally as well as domestically. As recently as October, Spain experienced a year’s worth of rainfall in a day, sparking intense flooding that left scores dead and farm fields decimated. In the U.S., the Ogallala Aquifer, which stretches across the Plains states and contains the nation’s largest underground store of fresh water, is disappearing.

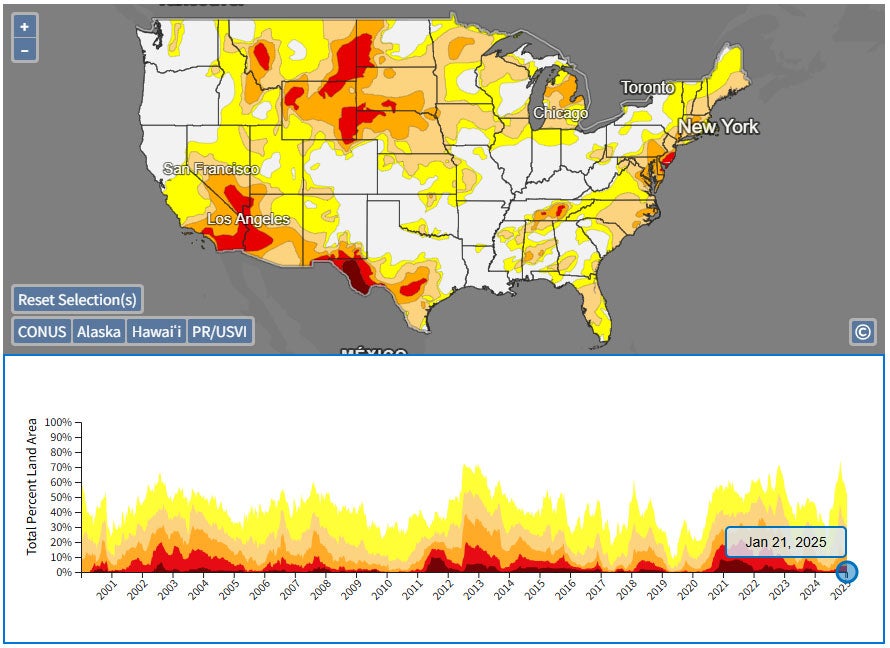

Much of the past five years has been a brutal stretch of some of the highest drought numbers in modern American history. And as recently as 2023, the United States experienced 28 distinct weather or climate events that each resulted in at least $1 billion worth of damage — most of which took place in the Wisconsin-to-Texas corridor and involved precipitation in a significant way.

The mega-drought in the southwestern U.S. has drawn attention to the increasing challenges for irrigated cropland as water supplies decline and demands from a multitude of users increase, American Farmland Trust explained in its 2023 report titled, Farms Under Threat 2040.

The urgency for agriculture is less about who to blame and more about how to cope.

“Innovation for climate resilience can come from small, disruptive innovators who are just entering the space, and it can come from established entities who already have a lot of experience and huge R&D,” said Sarah Garland, the founder and executive director for the Triple Helix Institute for Agriculture, Climate, and Society. “It’s extremely encouraging that we’re seeing these players in the agriculture space prioritizing climate resilient traits.”

Recently, the World Resources Institute nonprofit research organization said that about one-quarter of the world’s crops are grown in areas where the water supply is highly stressed, highly unreliable, or both. This is important because plant-water relations are susceptible to extreme changes in temperature and precipitation, even more so than from changes to mean climate. Depending on the stage during which water resources become a stressor, growers may see leaves begin to curl, impacts to the angle of roots, plant growth stunting, and likely lower yields.

High-calorie staples such as rice, wheat, and corn are commonly listed as among the most threatened by water instability, while tree nuts like almonds and pistachios are known to be extremely water intensive.

“Farmers live on the land, so they have an intimate relationship not only with their crops, but with the water for their crops,” said Charles Stack, a climate expert and co-founder of bioprocess engineering company NeoChloris Inc. “And so the lack of dependability and predictability of seasonal changes and rainfall is causing a lot of problems across agriculture.”

AFT projects that by 2040, nearly half of the water basins in the U.S. could experience “high” or “extremely high” water stress due to declining supply and increasing demands. The nonprofit also explained that rainfed cropland may feel the effects of dwindling surface and groundwater supplies.

Farmers will be forced to deal with the changes, whether through new growing tactics, the application of technological innovations, shifting production areas, or the evolving adoption of scientific opportunities.

Deepening the approach through science

Research, including advances in genetic engineering, are among the best tools that scientists say can help mitigate the extremes of water availability.

Garland highlighted some of the scientific work being done to help crops adapt to changing climate conditions said that “interest in this space is definitely growing.”

One advancement in Argentina took a gene from sunflower plants and inserted it into wheat to help make it better regulate the crop’s drought response. Elsewhere, research has gone into flood-tolerant rice (called Sub 1 Rice), which used molecular biology to identify genetic markers for the breeding process, making this variety more survivable when submerged.

“We need to develop regional-specific products,” Garland explained. “It is really an important direction moving forward, because obviously the crops we grow and the conditions that we have are so context specific.”

In the United States, even the shallow groundwater in the Corn Belt is being factored into the equations of water resources.

Understanding a process known as “precipitation recycling” — where moisture from plants, soil, lakes, and other landscape features is released into the atmosphere and returns as rainfall in the same area — is believed to be able to improve future rainfall predictions and provide more information for planting strategies and water resource allocations.

“This research shows how agricultural practices can modify regional climate, with implications for food and water security,” said Zhe Zhang, a scientist with the U.S. National Science Foundation National Center for Atmospheric Research and lead author of 2024 research titled, US Corn Belt enhances regional precipitation recycling.

The U.S. Corn Belt spans a dozen states in the Midwest and Great Plains, ranging from Ohio in the east to Nebraska in the west. The land surface, which had been a mix of tallgrass prairie and woodlands prior to European settlement, is now characterized by croplands with extensive irrigation.

“In an agricultural region like the U.S. Corn Belt where rainfall is critical,” Zhang said, “it’s important for both farmers and water resource managers to understand where the rain comes from.”

Looking at water as a resource is vital on the biotech side of the ag industry. Designing new seed varieties and hybrids to address changes in water availability and other forces related to climate disruption requires new capabilities not previously applied at scale in plant breeding.

The largest players in this space are working closely with growers to consider modern farming practices, environments, and product preferences to guide which technologies are advanced through R&D pipelines.

For example, many of Syngenta’s fungicides in recent years have auxiliary benefits centered around plant health. The ADEPIDYN technology found in the Miravis lineup works to address how the plant manages its water efficiency.

Additionally, major improvements in herbicidal controls are eliminating weed competition in the field, giving crop plants more opportunities to take up any water that becomes available.

Through the convergence of multiple technologies, such as artificial intelligence and machine learning models, Bayer Crop Science is accelerating and scaling its breeding pipeline to bring more value to customers, explained Rebecca Thompson, head of North America Plant Breeding at Bayer. She said that the company is managing more than 500 new seed products in its breeding pipeline every year — and that it is incorporating precision techniques and artificial intelligence to reduce the time to market by up to three years for these products.

“Instead of field testing all the possibilities and narrowing the funnel from there, 100 percent of our pipeline decisions start with customer insights and preferences, and we’re using AI to combine those insights with decades of rich internal data, so we can design the best candidates,” she explained. “Data models trained on years of germplasm performance data make it possible for breeders to anticipate a new hybrid or plant variety’s performance in thousands of micro-level agroclimatic and soil conditions, helping our breeders design and create products that better address farmers’ needs.

“This includes crops bred to perform in extreme conditions like too little or too much water,” she said.

One of these game-changing products from Bayer is the Preceon Smart Corn System — a short-stature hybrid that was designed to withstand extreme weather events. By growing to less than 7 feet in height (vs. 9 to 12 feet for a typical corn hybrid), Preceon corn has a decreased risk of lodging and is developed to produce a deeper root system, providing more efficient access to water resources and better absorption of nutrients, according to preliminary studies.

It’s a significant step change that also has a 5 percent to 10 percent smaller carbon footprint, even as efforts are underway to increase yield consistency.

“They have far more standability. Growers tell us they see their performance under different density conditions, their performance under different water availability conditions, and I think it’s going to be a real game changer in what acre you can get corn on,” Thompson said. “Some of our groundbreaker growers in 2024 were up at 350 bushels. That’s incredible production.”

Thompson noted that Bayer is still processing the data and understanding an innovation such as short corn prior to its broad availability. Preceon is scheduled to launch in the U.S. in 2027 and in Canada in 2029.

Farmers go into mitigation mode

The unpredictability that farmers are increasingly facing each year — as the heat differences between the North and South poles change and even states such as Illinois get wild swings in winter temperatures and snowfall amounts — makes it nearly impossible for proper seed planning.

“We need to prioritize adaptation strategies in tandem with efforts to reduce emissions,” Garland said. “That’s important for farmers being able to maintain productivity in a changing climate.”

Water-smart practices — including laser land leveling, rainwater harvesting, micro-irrigation, and crop diversification — are continually explored around the globe, though some techniques appear to have incremental costs that are financially prohibitive in their current state.

Some farmers are gravitating toward precise drip irrigation strategies to better focus their water usage — something that arid areas like Israel have done for generations — but even that requires a technology investment that isn’t often feasible in today’s low-margin farming economy.

“A big problem is the lack of government support to help farmers adapt to a changing climate,” Stack observed. “I’m convinced that that’s something we have to do. Farmers just can’t do it by themselves. They’re burdened with a lot of expenses and regulatory obligations, and we can’t expect them to be climate scientists and weathermen. We have to really kind of get in there and help them adapt to the hydrological cycle that we’re starting to see now. I strongly believe we need targeted financial assistance to help our farmers to adapt to the changing climate and hydrological cycle.”

There are several man-made factors propelling climate disruption in the U.S. and elsewhere. Agriculture — primarily cattle, agricultural soils, and rice production — contribute roughly 10 percent of the greenhouse gases in the U.S., according to the Environmental Protection Agency. However, that’s the smallest percentage among the EPA’s economic sector breakdown; energy, industry, and transportation are all two- to three-times larger contributors of GHGs nationwide.

For example, the natural gas and oil industry vent pure methane from their gas fields to the atmosphere when, to them, the price of natural gas is too low to spend the money to capture it. Yet people are more likely to hear about so-called “cow farts” from media outlets and politicians before they hear about criticism of the energy sector.

To be fair, the U.S. is such a big global contributor that even small percentages translate into big raw numbers. Arguably, though, farmers and the food, fiber, and fuel products they produce are the most important among those EPA’s main sectors, and they appear to be the most impacted by disruptions in water availability linked to a changing climate.

“The scale of the problem is so incredible that we can only solve it with concerted action, coordinated government policy, and application of best practices for water conservation in agriculture,” Stack said. “Otherwise, it’s only going to get worse, and we need to act immediately to help our farmers and farming communities.”

Researchers in World Resources Management have stressed “the impossibility of solving the water gap with single-oriented solutions, and argue that the water gap must be addressed through a sophisticated mix of policies, sufficiently flexible to accommodate the enormous causality of the ongoing water crisis.”

But in that publication, scientists go on to say how efforts to heal the symptoms of water exhaustion are partly based on geography and must consider measures that involve local interests and global scenarios. This includes opportunities for green infrastructure, lifestyle diversification and adaptive strategies, economic tools, and geopolitics and governance.

Independent stakeholders such as AFT agree about the complexity of potential solutions.

“Even if water is still available for supplemental irrigation on rainfed cropland, and new cultivars selected to maintain the original growing period under warming can balance the effects of moderate warming (3.6 F), these two crop management options may not fully compensate for the impacts that greater levels of warming beyond 3.6 F will have on food production,” AFT’s Farm Threat report said.

The ag research, germplasm, crop protection, agronomy, and digital sectors are all already highly involved.

The collaboration in these areas “allows us to ask way more questions than we otherwise could, because you can’t plant in every single field and every option and every environmental condition,” said Thompson, the Bayer scientist. “But we can use all that collective data with the imaging, the satellites, and our sensors to build models to help us understand how our germplasm is going to perform.”

This kind of data, she added, is what will allow “us to really make this paradigm shift that actually is what’s helping us to be able to have products that can be successful in these extreme environments.”

They are being done in conjunction with steps that U.S. growers have been naturally adopting as part of farmland sustainability and financial soundness: steps such as precision input control, reduced tillage, cover cropping, investment in more climate-friendly biofuels, and even reusing oil industry wastewater. Farmers are concerned about water availability because it presents an obstacle to a family’s primary agricultural asset, and they’ve been addressing it in many ways, whether it’s a primary motivation or not.

And because of these efforts, many people advocate for more farmers to be present in the dialogue and decision making about climate-related impacts and resources.

Still, Stack at NeoChloris Inc. offers a largely grim assessment of the current status of agricultural water and whether it’s a crisis that can be corrected.

“There’ll be parts of the United States that have been farmed for generations that will not be farmable anymore. They will not be arable lands,” he said. “And we’re seeing desertification. We’re seeing traditional crops being burned up out in the fields. It’s pretty sad.”

Ryan Tipps is the founder and managing editor of AGDAILY. He has covered farming since 2011, and his writing has been honored by state- and national-level agricultural organizations.