If you’ve ever thought angel hair pasta was too hefty, University College London researchers have just raised (or lowered?) the bar with spaghetti 200 times thinner than human hair.

Measuring a mind-boggling 372 nanometers, this “nanopasta” is officially the skinniest carb in existence. But before you start planning a microscopic dinner party, this spaghetti isn’t meant for eating. Instead, it’s poised to revolutionize medicine and industry, potentially healing wounds and regenerating bones faster than your nonna can say “mangia!”

The project, led by master’s student Beatrice Britton, involved using a technique called electrospinning. The researchers used an electric charge to pull threads of flour and formic acid through a needle. The result? Spaghetti so fine it’s invisible to the naked eye.

“It’s literally spaghetti, just much smaller,” said Dr. Adam Clancy.

For comparison, the next-thinnest known pasta is Sardinia’s su filindeu (“threads of God”), handmade by artisans and measuring a comparatively chunky 400 microns wide — 1,000 times thicker than this new creation. But unlike its heavenly counterpart, nanopasta wouldn’t survive a boiling pot.

“It would overcook in less than a second, before you could even take it out of the pan,” admitted co-author Professor Gareth Williams.

So, what’s the point of spaghetti you can’t eat? Nanofibers like these have huge potential in wound healing, as their porous structure lets moisture in while keeping bacteria out. They can also mimic the body’s extracellular matrix, making them ideal for tissue regeneration and drug delivery. Traditionally, creating nanofibers from starch requires intensive processing of plant materials, but the team’s method skips the energy-hungry purification step by starting with regular flour.

Of course, making spaghetti this small wasn’t as simple as raiding the pantry. The researchers had to use formic acid to break down the starch’s molecular spirals into smaller units suitable for nanofibers.

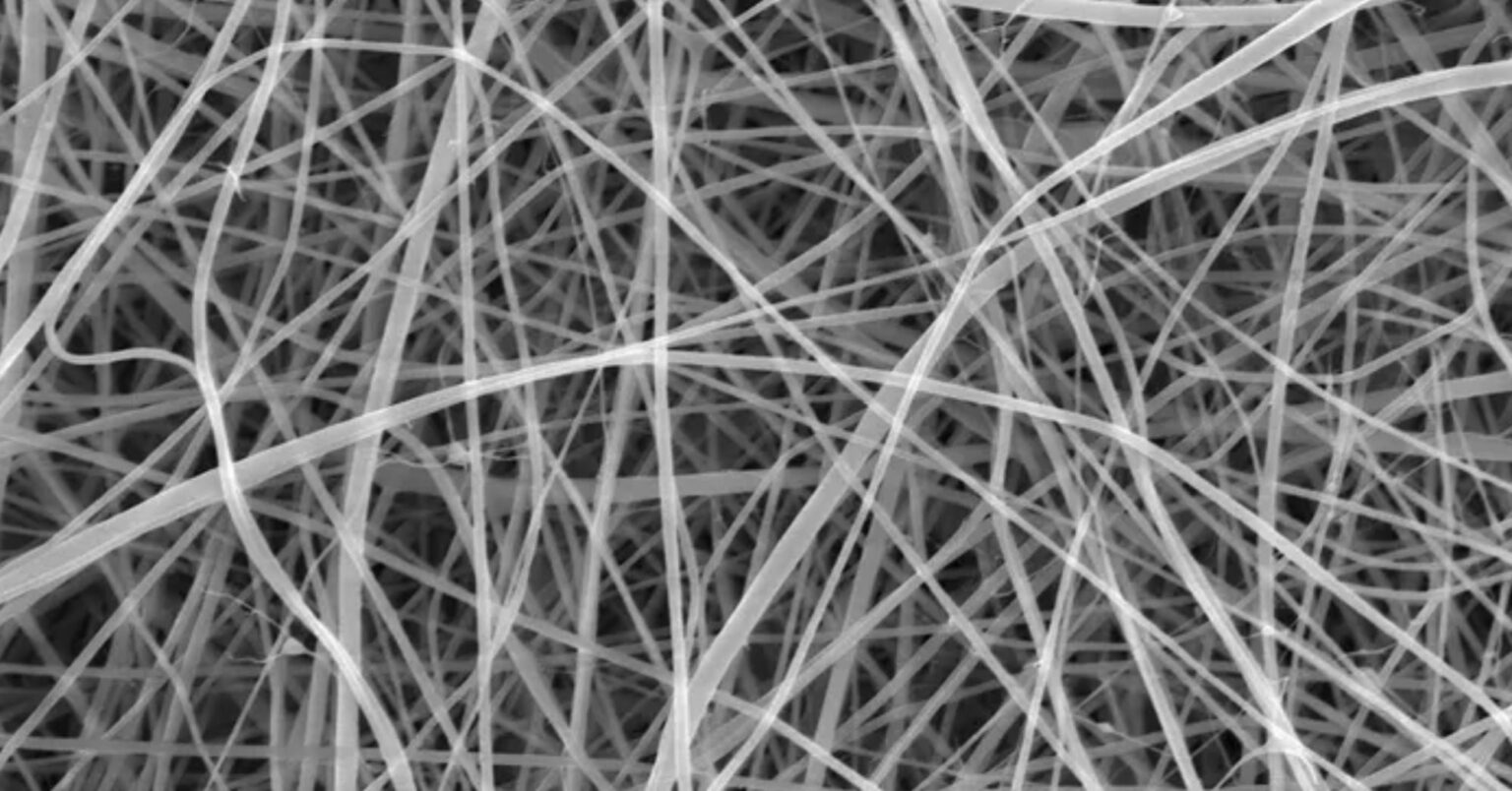

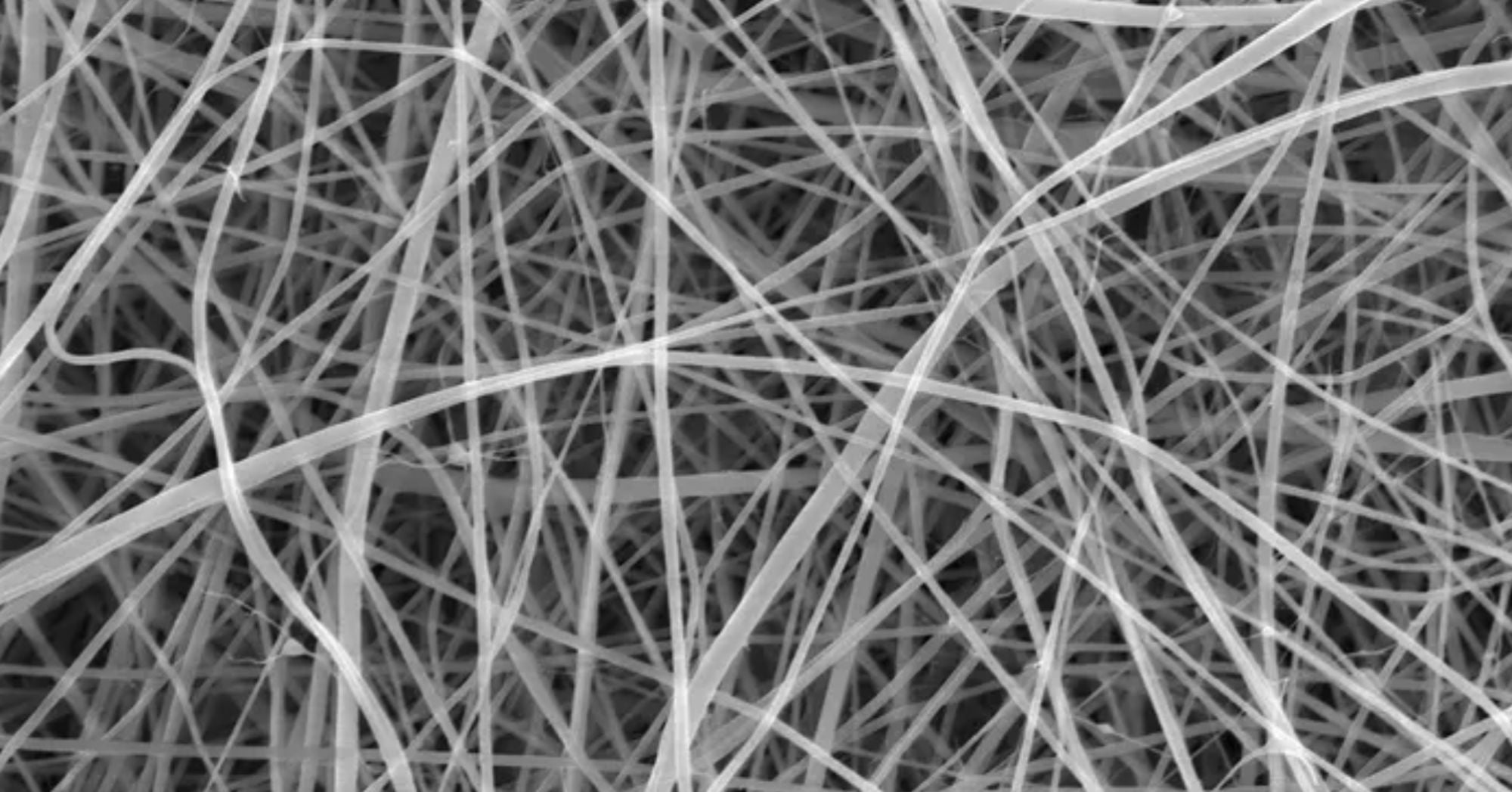

The acid then evaporated mid-flight as the spaghetti strands flew through the air to a metal plate, where they formed a mat of fibers about 2 cm wide. This process required hours of careful heating and cooling to ensure the mixture had just the right consistency –essentially slow cooking but for science.

While nanopasta won’t be making its way to your favorite Italian restaurant anytime soon, its potential to revolutionize medicine and materials science is enormous. And who knows? Maybe one day we’ll look back at regular pasta as embarrassingly thick — like VHS tapes or rotary phones. Until then, this spaghetti remains a dish best served … under a scanning electron microscope.