Food deserts — areas where access to affordable, healthy food is limited — have become a symbol of the systemic inequality in our food systems. While the problem has persisted for decades, the USDA 1890 National Scholars Program is cultivating a new generation of leaders determined to address this issue and make nutritious food accessible to all.

This program, launched by the U.S. Department of Agriculture, offers full scholarships to students at historically Black land-grant universities. Created under the Second Morrill Act of 1890, historically Black land-grant universities have played a significant role in educating Black Americans in agriculture, science, and technology.

Now, through the USDA 1890 National Scholars Program, students have the chance to receive not only an education but also hands-on experience within USDA agencies, ultimately shaping them into the leaders who will tackle the challenges of food access and agricultural sustainability.

The history of the 1890 National Scholars Program

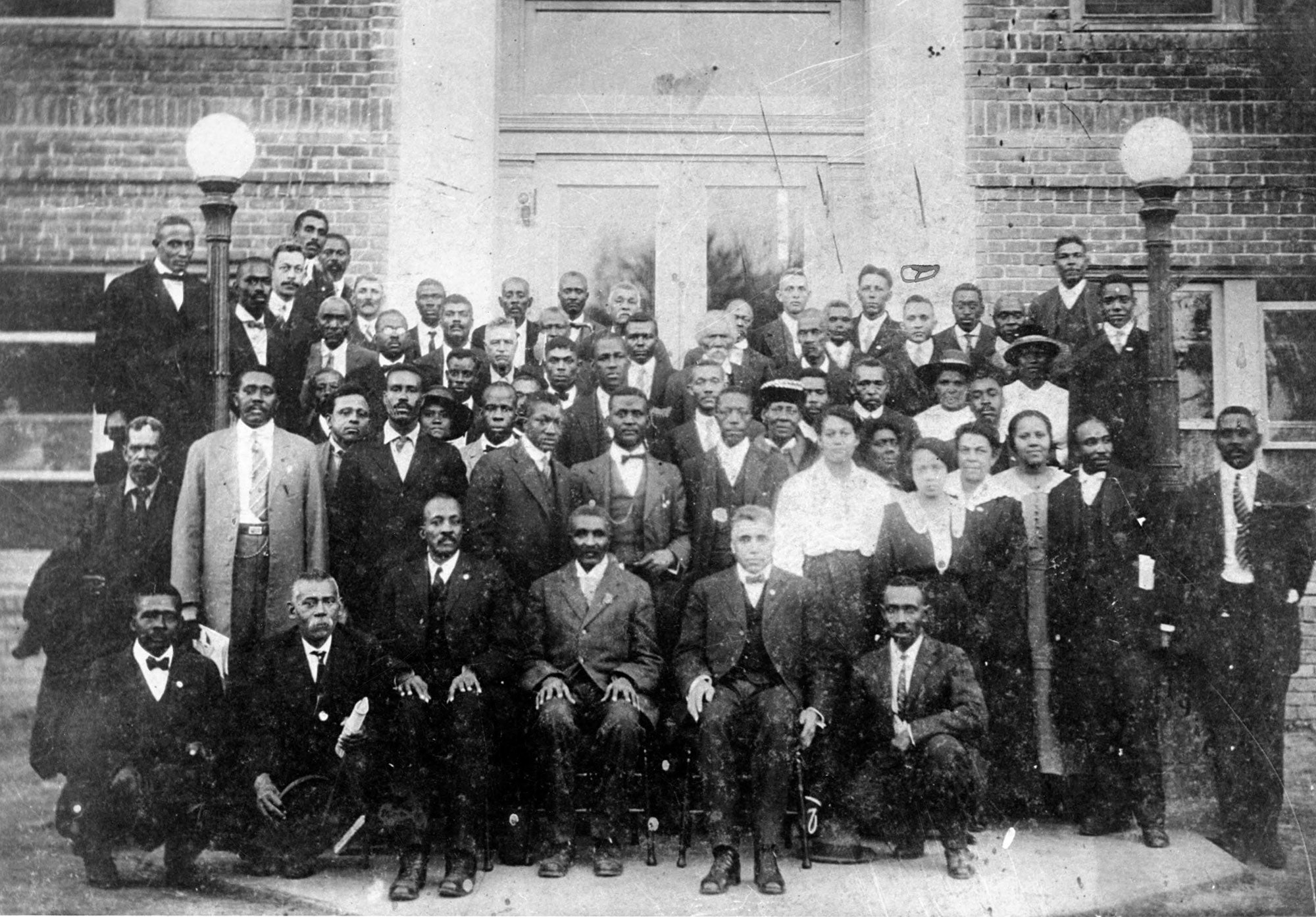

To fully understand the significance of the USDA 1890 National Scholars Program, we must first take a step back and examine the historical context from which it emerged. The Second Morrill Act of 1890, signed into law by President Benjamin Harrison, established land-grant colleges in Southern states. This, to provide higher education opportunities for Black Americans. These institutions, which included Tuskegee University, Florida A&M University, and Southern University A&M, were designed to address the educational disparities faced by African Americans in rural areas.

At that time, many African Americans were excluded from mainstream educational institutions, and the Second Morrill Act aimed to provide them with access to higher learning in fields that were critical to the nation’s economy. These land grant universities have since become pillars of education in the agricultural sciences, producing generations of Black professionals who have gone on to shape the agricultural sector and contribute to the broader economy.

The USDA 1890 National Scholars Program is a direct extension of this historical commitment. The program aims to increase diversity in the USDA workforce, as the Second Morrill Act had done for higher education, by offering scholarships to students attending these historically Black land-grant universities; like a pipeline of success to fuel our federal agencies of agriculture with people who reflect the communities they serve.

A personal commitment to change: Reese Baker

Reese Baker, a junior at Southern University A&M in Baton Rouge, Louisiana, is one of the many scholars benefitting from this program. Raised in the Houston, Texas area, Baker grew up in a community where fresh produce was hard to come by. It was an experience that stuck with her and shaped her commitment to improving food access.

“I was drawn to USDA and how everybody is unified with the goal of helping the world we live in,” Baker said.

This personal connection to the issue pushed her to major in business agriculture with a focus on supply chains and marketing. “I wanted to have a scholarship where I knew I could have job security and also do something I’m passionate about,” she explained.

The USDA 1890 National Scholars Program plays a crucial role in educating the next generation of agricultural leaders. By offering full tuition, fees, room and board, and providing internship opportunities at USDA agencies, the program ensures that these students not only receive an education but also gain practical experience in the field.

For Baker, this has meant internships with USDA’s Farm Service Agency, where she’s gained valuable insights into how agricultural policies work at a national level, impact trickling down to state and local agencies.

A personal commitment to change: A call to action for us all

Baker’s story is just one example of the kind of talent the USDA 1890 National Scholars Program is cultivating; talent that will play a pivotal role in addressing the challenges of food access across the country. This exposure to various facets of the agricultural industry allows scholars to gain the skills needed to drive meaningful change. Whether working in research, policy-making, or hands-on agricultural practices, the scholars of the 1890 National Scholars Program are positioned to become the problem-solvers who will shape the future of agriculture.

However, it’s clear that the challenges surrounding food access will not be solved by a single person or policy. The issues of food deserts, inequality, and sustainability are deeply rooted in our society and require a multi-faceted approach driven by innovation, empathy, and commitment. The USDA 1890 National Scholars Program is providing the foundation for a new generation of agricultural leaders, like Reese Baker, who are determined to break barriers and transform the systems that perpetuate these inequalities. But the work does not stop with them. The work calls upon all of us to support and nurture the leaders who are working to bring fresh, healthy food to every corner of our nation.

The future of agriculture is in the hands of those who dare to dream of a better, more equitable food system, and it is up to each of us to contribute to that vision. The question is: Where and when will we be part of the solution?

To learn more about Reese Baker and other scholars of the USDA 1890 National Scholars Program, please go to www.usda.gov/partnerships/1890NationalScholars.

Bre Holbert is a past National FFA President and studied agriculture science and education at California State-Chico. “Two ears to listen is better than one mouth to speak. Two ears allow us to affirm more people, rather than letting our mouth loose to damage people’s story by speaking on behalf of others.”